Tools of the trade

Danielle Dray looks at innovations in ophthalmic instruments

Danielle Dray

Museum Collections Coordinator, Surgeons’ Hall Museums

Our latest exhibition examines the establishment of ophthalmology as a surgical specialty. By exploring our collections, we have been able to trace the history of ophthalmic instruments and discover the innovations that have been made over the centuries.

The earliest form of ophthalmic surgery, known as couching, used a needle to push a cataractous lens backwards into the vitreous cavity of the eye. Since then, there have been constant efforts to improve the tools and techniques used to treat cataracts.

Due to the delicate nature of the anatomy of the eye, surgeons needed to rely on efficient instruments for accuracy. The smallest changes to their size, shape and weight could have a significant effect on efficacy. Design of surgical instruments became a matter of prestige, but while many ophthalmic surgeons devised their own instruments, only a few gained wider popularity.

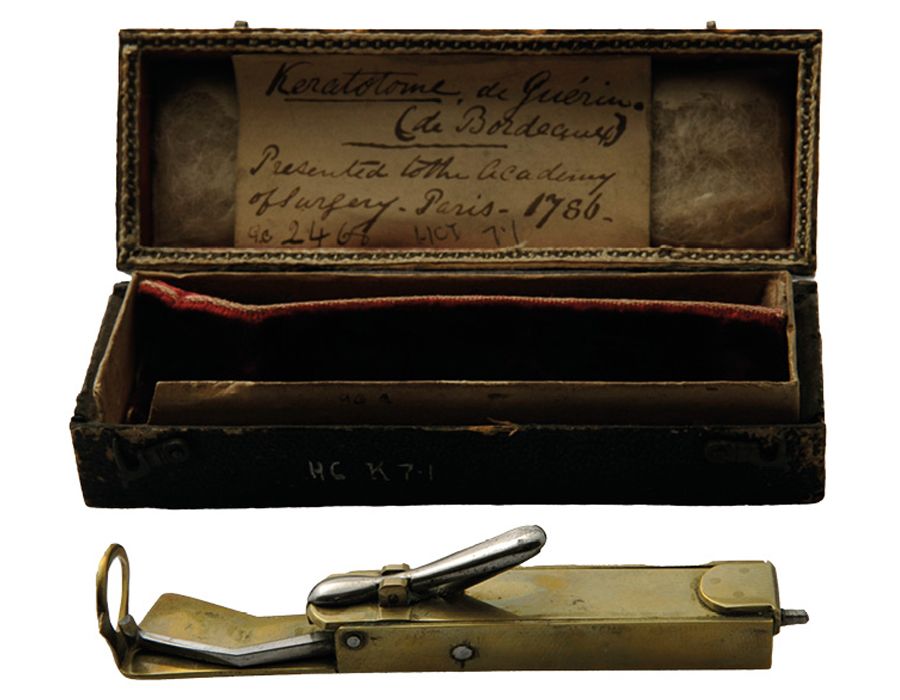

With topical anaesthetic for eye surgery not introduced until 1884, speed was essential in performing a successful operation. In 1786 Pierre Guerin invented a spring-loaded cataract knife. The triangular keratome, when released, cut the cornea in a fraction of a second. However, it was still required to widen the incision with scissors, a slow and painful procedure.

Consequently, the design did not gain popularity and examples of Guerin’s invention are now quite rare.

The success of a lens extraction depended on the accuracy of the initial incision. In 1773 Augustes Gottlieb Richter described an improved method of cataract extraction, where the lens was pushed out of the eye with a needle by a single large incision made in the sclera with a knife.

Following this method, Georg Joseph Beer devised a specialised knife with a key innovation: the triangular blade. His design was not unlike a keratome, but Beer’s wider blade meant the imprecise use of scissors could be avoided.

Pierre Guerin's spring-loaded keratome

Pierre Guerin's spring-loaded keratome

“Mastery of the Graefe knife was considered a hallmark of excellence among ophthalmic surgeons”

Another significant advancement was made by Albrecht von Graefe in 1865. Graefe’s knife had a long and narrow blade, allowing for even greater precision. However, use of the knife required exceptional dexterity, and even until the late 20th century many surgeons preferred the keratome-and-scissors technique, which was now more viable with anaesthetics. Nevertheless, mastery of the Graefe knife was considered a hallmark of excellence among ophthalmic surgeons, with many considering the use of keratomes to be ‘for beginners’.

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, all ophthalmic tools were designed for intracapsular extraction, which removed the entire lens, including the capsule. Jaques Daviel first attempted extracapsular extraction in 1750 by scooping the lens from the capsule using a curette. However, his method was very imprecise and complications were common. Extracapsular extraction was largely discarded for the next 300 years.

It was not until 1962 that extracapsular extraction became feasible again, when cryoextraction was introduced by Charles Kelman. This involved using C02 to freeze the lens so it could be removed from the capsule intact. Cryoextraction was quickly supplanted by the use of phacoemulsification, which used ultrasonic instruments with an aspiration and irrigation system, allowing the lens to be emulsified and sucked out of the capsule through a very small incision. This is still used as the standard method of lens extraction and, notably, Graefe’s knife is still the preferred instrument for creating the initial incision.

Georg Joseph Beer's cataract knife and Graefe's knife will be on display

Georg Joseph Beer's cataract knife and Graefe's knife will be on display

The re-emergence of extracapsular extraction was a factor in the use of intraocular lens implants. Introduced by Harold Ridley in 1949, the implants were designed to restore the eye’s refractive ability. But the implants were unreliable because the lens capsule was not in place to support the implant. With new methods of extracapsular extraction, the lens capsule could be left in situ, and new designs of intraocular-lens implants with stabilising haptics meant lens-replacement surgery had better long-term outcomes.

Ophthalmologists today still strive for improvements in their tools and techniques. Advancing technology has allowed the use of lasers and high-power operating microscopes to aid surgeons. Cataract surgery is still one of the most common procedures carried out – who knows what the next innovation will be?

Examining the Eye: Medicine’s Oldest Specialty runs until Easter 2025