Surgical safety update

Medication mismanagement

A 57-year-old female patient with a background history of type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was admitted with abdominal pain and jaundice. An MRCP was performed, which showed cholecystitis and a dilated common bile duct (CBD) with distal stones. The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with exploration of the CBD, which was repaired and a T-tube left in the duct. Two days postoperatively she became drowsy and delirious with Glasgow Coma Scale score of 9. She developed an acute kidney injury, metabolic acidosis and ketosis. At this point it was noted that the patient had continued to receive empagliflozin since her admission and this had led to euglycaemic ketoacidosis.

Reporter’s comments

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (such as canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin and ertugliflozin) are a relatively new class of oral drugs for the management of T2DM. We should be aware of potential side-effects. Surgical teams should work closely, where possible, with pharmacy teams to ensure medicine reconciliation prior to admission to reduce medication errors. It would be helpful to introduce systems for people with diabetes to report changes to their medication between their preoperative assessment and date of surgery. As per Centre for Perioperative Care and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges guidelines for perioperative care for people with diabetes mellitus, the following are recommended:

1. SGLT2 inhibitors should be withheld 48 to 72 hours prior to all major surgeries. Plasma glucose levels should be closely monitored perioperatively.

2. Vigilant postoperative assessment for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), even with normal plasma glucose.

3. These drugs should be restarted only when the patient is eating and drinking normally postoperatively.

CORESS comments

Awareness of serious side-effects of medication is vital, especially in emergency care when preoperative planning is not possible. In March 2022, the British Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society issued a Patient Safety Alert regarding the risk of harm from the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, which outlines the importance of understanding the risks associated with this class of medication.

Patients may not remember or understand the risk, especially if they are on a number of different medications, so increased awareness among healthcare professionals is important.

Safety alerts embedded into digital prescribing systems should alert prescribers to the risk of euglycaemic DKA in fasting patients.

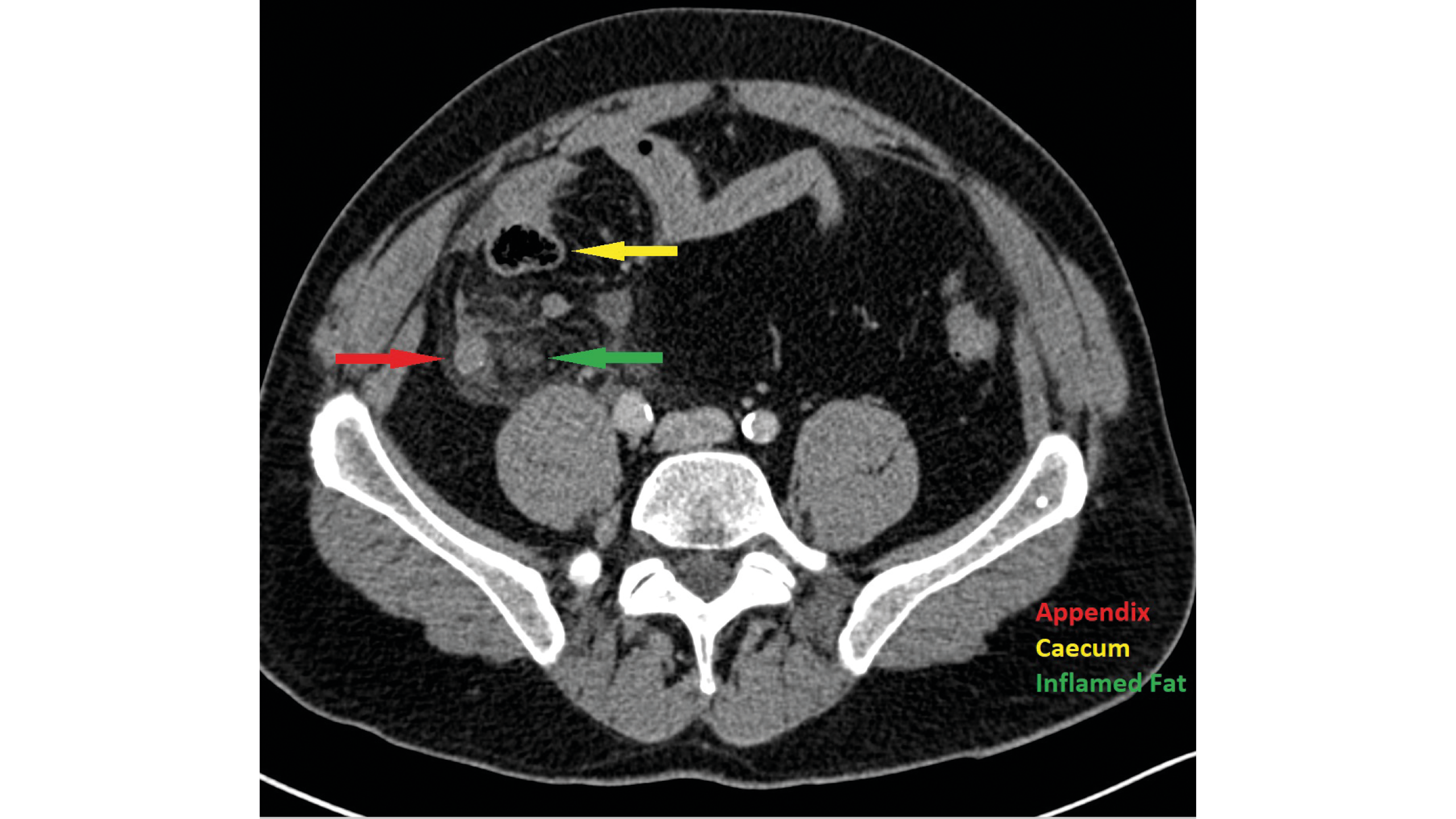

CT showing appendix and inflamed fat. Finding the appendix during surgery can be a challenge if inflammation obscures anatomical plains

CT showing appendix and inflamed fat. Finding the appendix during surgery can be a challenge if inflammation obscures anatomical plains

Wrong side consent form

A 15-year-old boy with a solitary left testis was referred for consideration of a testicular prosthesis. A right testicular remnant had been removed from the groin in infancy, confirming a diagnosis of testicular regression. He was seen in clinic with his parents on two occasions.

At the first visit he was examined and found to have a normal post-pubertal testis in the left hemiscrotum. He received counselling regarding the potential complications associated with insertion of a testicular prosthesis and a further review advised to allow time to think about whether he wanted to go ahead.

At the second review the patient advised that he wanted to have a prosthesis inserted. As he was considered to be Gillick-competent, a consent form 1 was completed using an electronic consent platform and the young man was keen to sign the form “there and then” even though the option of accessing the form remotely was offered.

On the day of surgery, the young man was seen by an astute trainee, who examined the patient, reviewed the notes and the operating list, and noted that the consent form stated insertion of a left-sided prosthesis instead of a right-sided one. The incorrect form was cancelled, a new form created and the procedure completed on the correct side.

Reporter’s comments

The consultant made an error when ticking the box for the side on the electronic consent form and this was not noticed by the patient. He may have been embarrassed and keen to complete the consultation promptly, although it may be that, having always had a solitary testis, he was not sure which side it was on. The registrar was not planning to tell the consultant of their error, although the consultant spotted it as there were two consent forms visible in the electronic system at the sign-in.

This was a valuable lesson for both the consultant and for the registrar as covering up a near miss is a missed opportunity to learn. Of note, the electronic consent platform has since improved the ‘visibility’ of which side is selected due to concerns raised by other users at our Trust.

CORESS comments

The revised national safety standards for invasive procedures (NatSSIPs 2) involve eight sequential steps and highlight the importance of communication and situational awareness, both of which are relevant to this case. The ‘consent, procedure verification and site marking’ step must be undertaken by a person with knowledge of the procedure and with access to the medical records, and should involve the patient. The trainee made a ‘good catch’, as the patient may have been unsure of the side of the procedure, distracted by the approaching procedure or reluctant to speak up.

While the side error may have been obvious before an incision was made in this scenario, identification of the error at the earliest possible stage benefits the entire team. The value of reporting near-miss incidents such as this should not be underestimated.

An appendicectomy that wasn’t

A 25-year-old female presented with right iliac fossa pain (RIF) and a high temperature. Appendicitis was diagnosed, a laparoscopic procedure performed and the patient prescribed postoperative antibiotics. The patient was discharged on day three postoperatively, but readmitted on day six with pain, fever and high CRP of 320. CT was performed and an abscess identified in the RIF, which was drained percutaneously. The patient had a postoperative ileus and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) was started.

She recovered slowly, requiring TPN for two weeks.

One month after discharge the patient attended the outpatient clinic complaining of ongoing pain. Additional CT was performed, which surprisingly identified an inflamed appendix. The histology of the tissue removed at the initial operation was reviewed and the tissue was found to be inflamed fat, with no appendicular tissue. Review of the previous CT also identified the appendix.

Reporter’s comments

The experience of the surgeon is important when treating appendicitis and junior surgeons need to be supported in all cases. CT reporting was misled by the clinical information and the histology department could have alerted the surgical team that the specimen did not confirm the appendix. As usual, the hardest thing about appendicitis is finding it!

CORESS comments

Appendicectomy can be a challenging operation, especially if significant inflammation obscures anatomical plains. While the difficulty of the initial operation may explain the failure to remove the appendix, there were two opportunities to identify the problem, both of which were missed:

1. The histopathology report was clear that the appendix was not within the analysed specimen, but the report was not seen in a timely manner. While the system by which abnormal results were flagged to the clinical team was presumably inadequate, this is a reminder that relevant results should be checked when a patient is not making the expected recovery.

2. The report of the initial CT was, however, incorrect. This represents a scenario of ‘seeing what you expect to see’ – that is, assuming the appendix was absent based on the clinical history. The maxim ‘assume nothing’ seems pertinent in this case.

|

Reference 1. Laor E, Palmer LS, Tolia BM, Reid RE, Winter HI. Outcome prediction in patients with Fournier’s gangrene. J Urol 1995 Jul; 154(1): 89–92. Harriet Corbett Programme Director on behalf of the CORESS Advisory Board Frank Smith CORESS Board of Trustees We are grateful to those who have provided the material for these reports. The online reporting form is on our website, coress.org.uk, which also includes previous Feedback Reports. Published cases will be acknowledged by a Certificate of Contribution, which may be included in the contributor’s record of continuing professional development.

CORESS is an independent charity supported by AXA Health and the MDU |