Pioneering surgery

Matt Harris and Emma Howie look at current challenges in robotic training and aims for the future

Matt Harris: General Surgical ST, Cancer Research UK PhD Fellow, ASiT Honorary Secretary,

ASiT Robotic and Digital Surgery Trainees’ Committee Chair

Emma Howie: General Surgical ST, Clinical Research Fellow, RCSEd Trainees’ Committee

Following the first installation of a da Vinci Surgical System at St Mary’s Hospital in London in 2001, the prevalence of robot-assisted surgery (RAS) has increased exponentially1. There is no pan-specialty UK registry for RAS, but data suggest there are now more than 100 hospitals providing RAS procedures.

RAS is expanding across surgical specialties, with urology, general surgery and gynaecology utilising the technology most. However, despite this increasing prevalence, there is no mention of robotics in the current JCST curriculum.

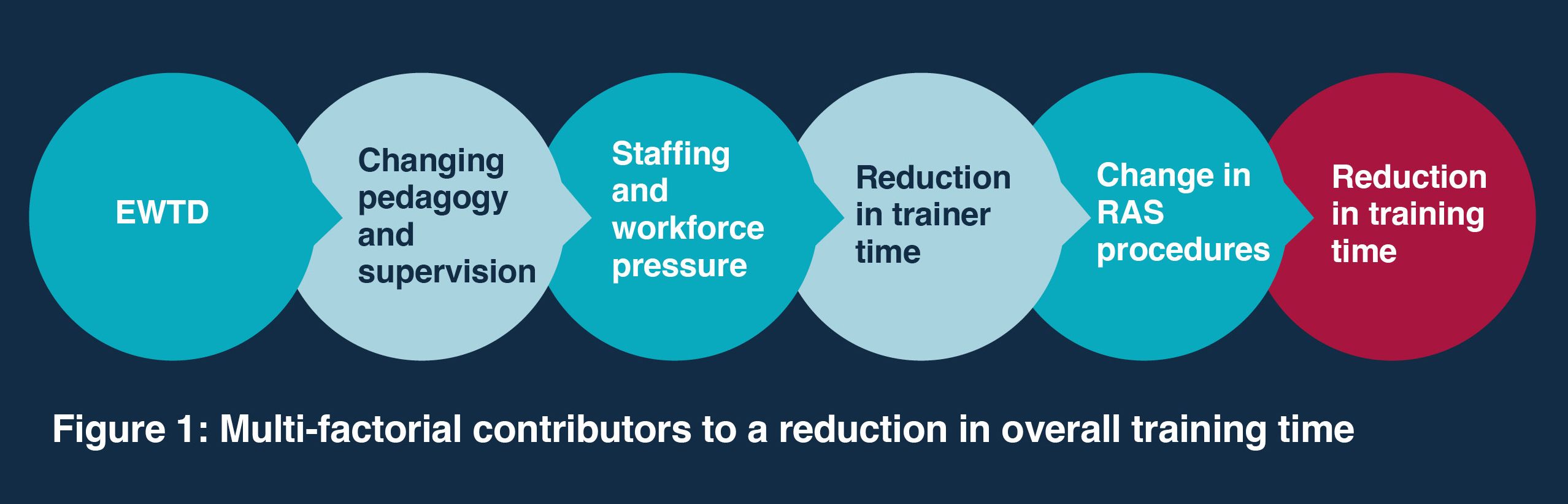

Surgical training has drastically changed in the past few decades due to the COVID-19 pandemic, changing training pedagogy, the disappearance of the firm, an NHS under pressure and increasing service commitments (see Figure 1). This is compounded by a lack of time for trainers. The recent JCST Trainer Survey revealed the majority of academic educational supervisors do not have sufficient time for trainee supervision2.

The current situation

The emergence of new technology, the increasing importance of RAS and the reduction in training time provide three unique challenges.

Lack of resources and inequity of access

Novel technology is expensive and RAS is no exception. The prohibitive high financial cost of robotic systems results in a minority of hospitals providing robotic exposure or experience, with clear geographic variance. This is exacerbated for trainees, with additional factors including inter-deanery variances and the differing prevalence of RAS between specialty and rotational training1.

As many as 90% of trainees view robotics as integral to their future career, but more than 70% have no access to robotic training, while 74% of trainees would value greater access to robotic training3.

UK trainees have considerably less exposure to RAS compared with US trainees.

More than 85% of UK trainees state they have inadequate RAS training compared with 35% of US trainees. Worryingly, 91.2% of trainees in the US have performed more than 15 cases as primary surgeon compared with only 3.4% of UK trainees4.

Training opportunities

With the introduction of new operative techniques and a finite resource of training cases, there will inevitably be rationing of opportunities. Senior clinicians are prioritised to progress with their own RAS training, potentially impacting training opportunities for trainees.

Trainees commonly find that cases they would previously have performed are being redistributed to trainers still reaching RAS proficiency, further reducing training opportunities3.

The robotic curriculum (or lack thereof)

There is currently no accepted, standardised RAS training programme or curriculum within the UK. In the US the Robotics Training Network has an accredited curriculum, but no such resource exists in the UK5. A lack of inclusion in the surgical curriculum encourages barriers to promoting equal, standardised access to an evidence-based robotic training programme, as highlighted by the recent Future of Surgery: Technology Enhanced Surgical Training Report6.

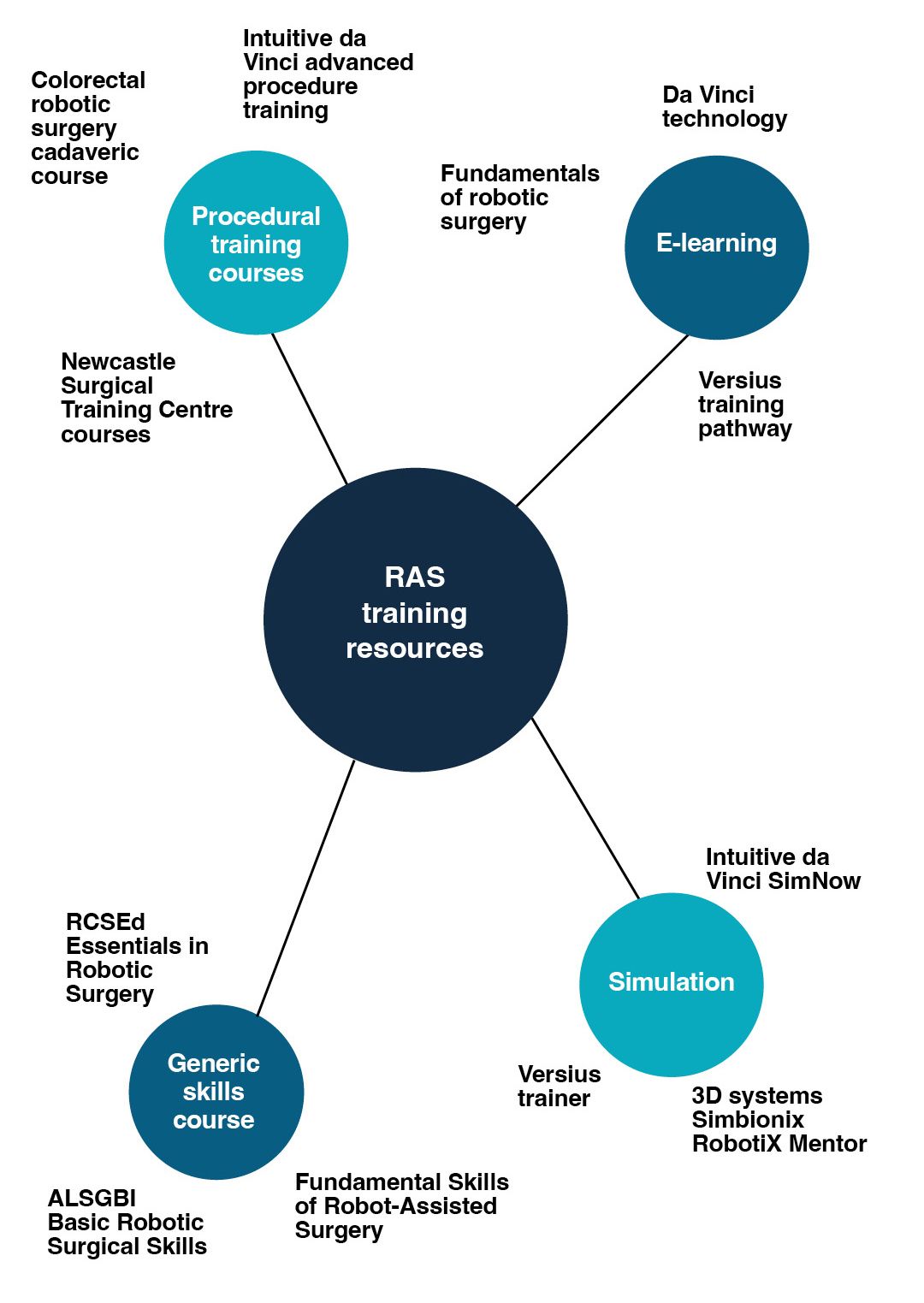

The expiration of key patents had led to expansion of the available platforms. In the NHS there are now three platforms in use: da Vinci (Intuitive), Versius (CMR) and

Hugo RAS (Medtronic). These platforms have key operational differences leading to individual industry-led, platform-specific training pathways. Additionally, there are specialty-specific and surgical society-led training programmes (see Figure 2). This confusing menu of options may contribute to variations in competence and access to training.

Proposed solutions

To overcome these challenges a collaborative and evidence-based approach to developing solutions must be utilised, including the integration of a structured robotic training pathway into the curriculum. With advances in

novel surgical technology, the integration of technology-enhanced surgical training – including surgical sabermetrics, extended reality

(XR) simulation and video-based assessment (VBA) – will maximise the efficiency of an integrated robotic training curriculum.

We propose a successful future

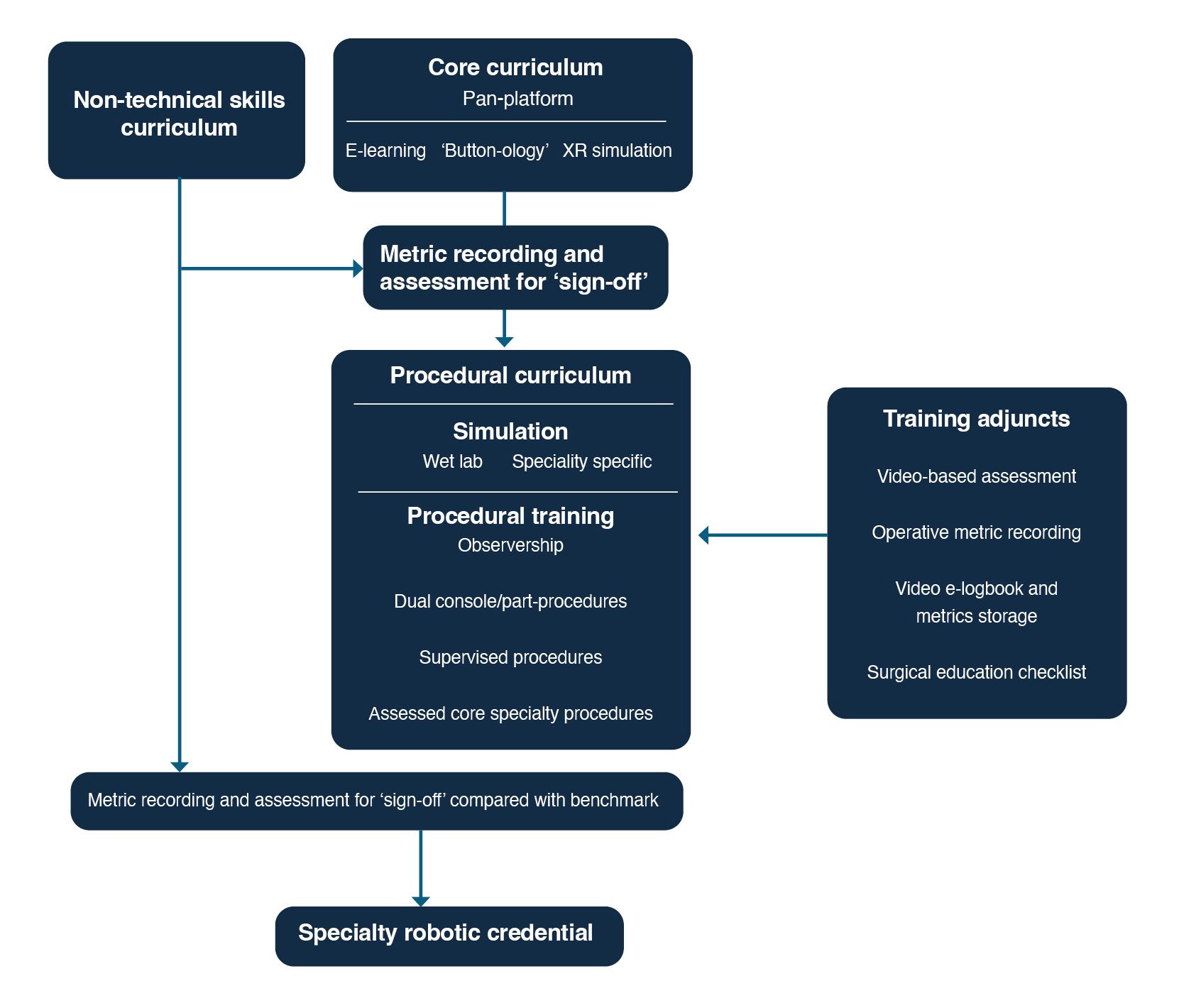

of RAS training that may look like the following, with training divided into three areas (see Figure 3).

Core curriculum

Early RAS training requires an understanding of the technical aspects of the platforms. Trainees can utilise e-learning modules, basic simulation and XR simulation. Operative, objective metric recording and assessment should

be built into a standardised core skills curriculum leading to a

final sign-off.

Trainees can progress through early training at their own pace, without the need to compete for theatre time. This pan-specialty core curriculum would be available to core and specialty trainees. To reduce inequality of access, a deanery/regional model of delivery should be instigated7.

Procedural or specialty-specific curriculum

Following completion and sign-off of the core curriculum, trainees can progress to a procedural or specialty-specific curriculum. Wet lab simulation can bridge the gap between core and procedural

training. Direct observation and assisting are essential aspects of surgery, so time should be spent in theatre observing before progression to bedside assistant.

Subsequently, a stepwise transition from observation to dual-console, part-procedure operating to supervised operating should take place. VBA and validated, structured training methods can be used as assessment adjuncts and evidence of competence when rotating. Standardised performance assessment, incorporating objective metrics, VBA and direct observation of key procedures, can lead to robotic credentialing.

Non-technical skills curriculum

The RCSEd is a world leader in non-technical skills for surgeons (NOTSS). Non-technical skills are critical, with the complexity necessitating specific robotic NOTSS. This training can take place alongside the core and procedural curriculum and form part of the assessment and sign-off of each stage. The necessary incorporation of team training empowers the entire team to improve technical and non-technical skills.

Next steps

It is non-negotiable that trainees should be involved in the development of a robotic curriculum and structured training pathway. Key stakeholders should work together to make the future bright for RAS training, with work from the RCSEd Robotic Surgery Taskforce, intercollegiate collaboration and pan-College, trainee-led organisations such as the Association of Surgeons in Training and the Robotic and Digital Surgery Trainee Committee taking the first important steps in improving RAS training.