Pioneering spirit

Jacqueline Cahif explains Edinburgh’s pivotal

role in the training of the first woman to qualify

as a dentist in the UK

Jacqueline Cahif: RCSEd Archivist

In 1885 an editorial appeared in the British Journal of Dental Science with a somewhat disparaging view of women’s capacity to work as professional dentists. It concluded, “to us it would appear likely that in England lady dentists will prove a development only of the far distant future, if at all”. I wonder if this editor was made to eat his words 10 years later when Lilian Murray (later Lilian Lindsay) became the first woman in the UK to qualify as a dentist.

The struggle for women’s entry to professional medicine and surgery is well covered in historical documents, but we hear less about early women pioneers in dentistry. Entering the male profession of dentistry was not for the faint-hearted, but it was a challenge she took head-on despite encountering some initial setbacks. For the London-born future dentist, it was Edinburgh that provided her with the opportunity.

Born in 1871, she was privately educated at Camden School for Girls and North London Collegiate School. Although her father died when she was only 14, leaving the large family financially constrained, her academic talents funded much of her schooling through successive scholarships. Her headstrong character was clear from a young age when her teacher Miss Buss refused her a further scholarship in 1889, thereby cutting her schooling short.

In her words: “Miss Buss was ardent in recruitment of teachers,” which ran at odds with the young student’s ambitions. After being informed by Buss: “I will prevent you from doing anything else,” she sharply responded: “You cannot prevent me from becoming a dentist.” She recalled: “I knew nothing about dentistry, but having stated boldly that I would be a dentist, there was nothing else to be done.”

Early photograph of Lilian Lindsay, née Murray. Date unknown

Early photograph of Lilian Lindsay, née Murray. Date unknown

This determination helped Lindsay deal with the next barrier. In 1892, at the age of 21, she approached the National Dental Hospital and School in London to enrol as a dental student, having spent the previous three years apprenticed to a registered dentist. Yet when she was greeted by the Dean of the School, Henry Weiss, he “did not permit me over the threshold” for fear of distracting the male students. Instead, she was interviewed on the pavement outside the school where Weiss refused to enrol her.

In later life she recalled this rejection as “hard but I had started on the road to dentistry and must not turn back”. Weiss advised her that the Royal College of Surgeons of England – who had introduced their Licentiate examination (LDS) in 1861 – would not admit women for examination. Thereafter she headed to Scotland, which was a shrewd move for several reasons.

At the forefront

Although the LDS in Scotland was introduced later than in England, Edinburgh had been at the forefront of dental education for some time and boasted some of the best dentists in the United Kingdom. Edinburgh surgeons had made attempts to include dentistry in their teaching since the 18th century, but this was very much an adjunct of general surgery. It took considerable efforts to persuade doctors that dentistry had its place alongside medicine, surgery and pharmacy.

The RCSEd had a key role in this process, and former President John Smith (1825–1910) introduced a course of lectures on Physiology and Diseases of the Teeth to students at the College in 1856. This was the first formal dental course in Scotland. Smith was later instrumental in getting the Dentists Act of 1878 passed into parliamentary law, and in 1879 the College established its first Dental Licentiate examination (LDS RCSEd).

Importantly, Smith was a key figure in the foundation of the Edinburgh Dental Hospital and School in 1879. At an Annual Meeting of the British Dental Association held in 1894, a year before Lindsay would qualify, she referred to it as “the most up-to-date school in the Kingdom”.

Conditions were more favourable in Scotland for women entering the medical professions, and in particular the Royal Colleges. In 1884 the Triple Qualification offered by the three Scottish Royal Medical Colleges was introduced. This allowed women to access examinations not available to them in university medical schools, and in 1886 Alice Ker became the first woman licensed in Scotland to practise medicine and surgery. (It was not until 1894 that Marion Gilchrist and Alice Robson became the first women to qualify in medicine from a Scottish university, graduating from the University of Glasgow, and in 1896 Mona Chalmers Watson became the first woman to graduate from the University of Edinburgh.)

After Lindsay’s unsuccessful interview in London she approached William Bowman MacLeod of the Edinburgh Dental Hospital, and was met with a more encouraging response: “Women are received on the same footing as men.”

That is not to suggest it was plain sailing for Lindsay once she arrived in Edinburgh. While meaningful advances had certainly been made, the medical world in Edinburgh was still relatively divided on the subject of women entering the professions of medicine, surgery and now dentistry. Edinburgh’s Medical Officer of Health and former RCSEd President Henry Littlejohn ridiculed her notions of entering the male world of professional dentistry: “You are taking the bread out of some poor fellow’s mouth.”

When she tried to pay the Treasurer of the Dental School for her class ticket he attempted to persuade her to return to London:

“A three-month ticket, you will be sure to give it up … and will be sorry when no money is returned.” However, she later recalled that the Treasurer, “exasperated with my determination, gave me the ticket”.

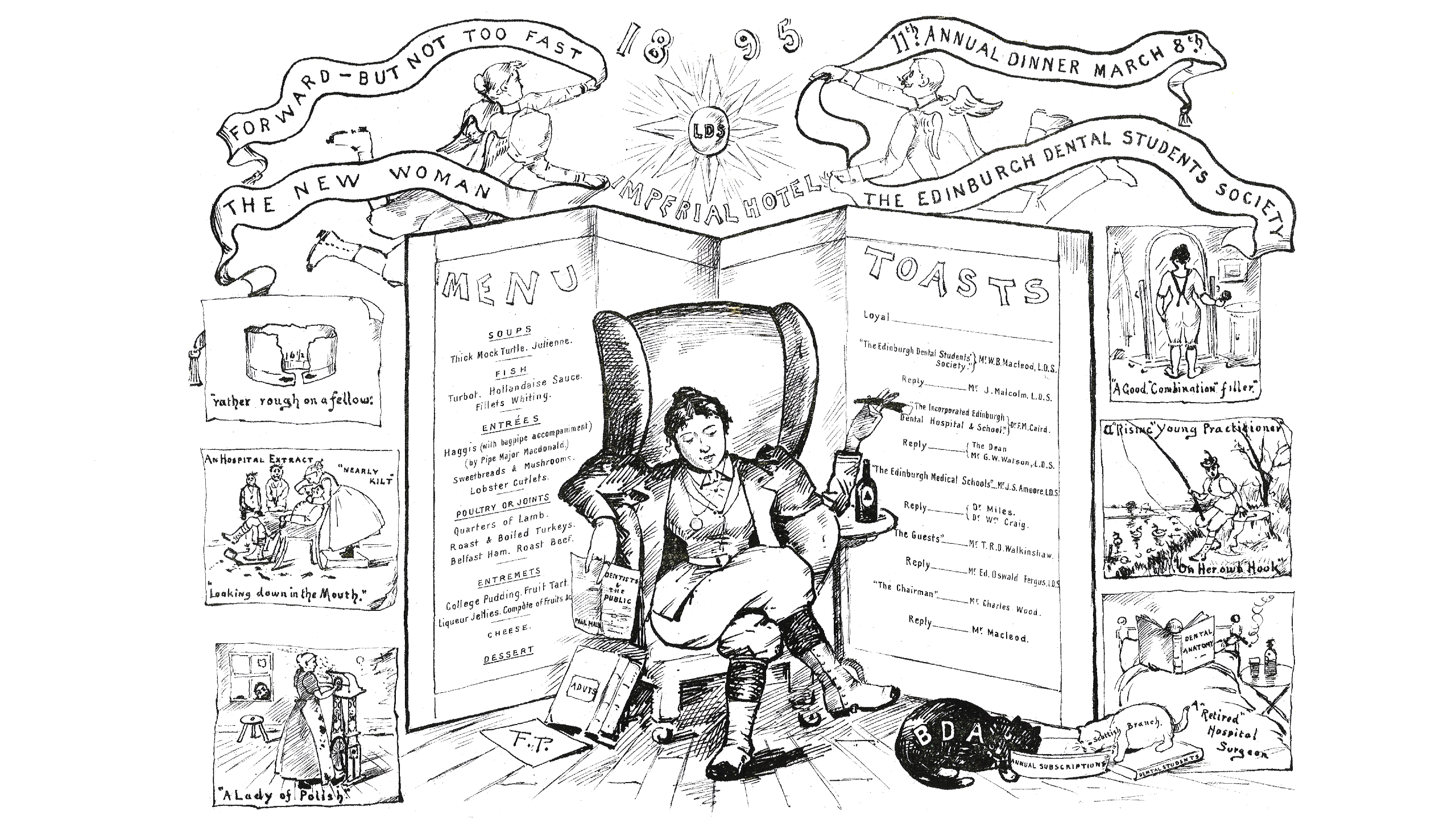

Inside cover of a menu dated 1895, the year Lilian Lindsay graduated, which was illustrated by a fellow student

Inside cover of a menu dated 1895, the year Lilian Lindsay graduated, which was illustrated by a fellow student

“Lindsay was able to take mixed-sex dental classes, unlike in the medical schools where mixing was not permitted. She went on to win a class medal in 1894”

kind colleagues

Despite being the only woman in her class, Lindsay found her fellow students “the kindest imaginable”. This was quite the departure from the experience of Sophia Jex-Blake and The Edinburgh Seven a couple of decades earlier. In 1870, after being subjected to a year-long campaign of abuse by their fellow male students, this culminated in the Surgeons’ Hall Riots when the women attempted to sit an anatomy exam. Despite successfully enrolling as students, they were later barred from graduating.

Lindsay was able to take mixed-sex dental classes, unlike in the medical schools where mixing was not permitted. She went on to win a class medal in 1894 despite being the only woman in her class. In later life she looked back on her student days as the “most joyous and carefree” time of her life, remarking “there were difficulties now and then, but looking back they do not seem so formidable as they may have appeared at the time”.

Love and dentistry

As always, nostalgia is often used to hide pain or particularly challenging obstacles in early life and should not detract from the barriers she would have been compelled to navigate to become the first women to qualify as a dentist in this country.

Any hostilities she encountered were partially mitigated emotionally by a supportive partner (and future husband) whom she met on her first day at the hospital – the dental surgeon Robert Lindsay. Their first meeting was far from love at first sight, and it is said that upon being introduced to Robert as a member of teaching staff on her first day as a student, her future husband declared that dentistry was not an appropriate occupation for a woman.

After passing the final LDS examination and qualifying in 1895 Lindsay returned to London, where she borrowed money to pay off her debts and set up practice in the city, as well as establishing a branch practice in the country. Robert joined her 10 years later when they were married. Despite her list of extraordinary achievements she remained modest and preferred to credit her husband: “Any use or good I may have been or have done is entirely owing to Robert Lindsay, his example and influence.”

She won an astonishing number of prizes and awards and held numerous Fellowships. In 1946 she was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Edinburgh and made Commander of the British Empire (CBE). That same year she became the first female President of the British Dental Association.

She was also sub-editor of the British Dental Journal for 20 years and produced her own impressive list of publications, including major historical works. She held many extra-curricular interests, and upon retirement established the library at the British Dental Association, where she immersed herself in her capacity as Honorary Librarian.

Like her contemporaries in the world of surgery (our first female Fellow Gertrude Herzfeld springs to mind), Lindsay strongly encouraged and supported junior women in her profession. Today, mentoring is still important for women in the early stages of their dental careers. She also championed continuing professional development when it was still a novel concept (outside America) and encouraged study clubs. She worked hard on promoting and advancing preventive dental work in young infants.

An inspiration to others

Recent statistics reveal the gender divide in dentistry has arrived at a near 50/50 split, and it is important to reflect on Lindsay’s influence. Taking inspiration from the earliest cohort of women to qualify as doctors, she laid the groundwork for future women in dentistry. As a student, she attended general surgery lectures at Jex-Blake’s school for women and was invited to have lunch with the medical pioneer. She found Jex-Blake to be more gracious than she expected and the event “a somewhat awe-inspiring function”. I wonder if it crossed her mind during lunch that, just as Sophia Jex-Blake inspired successive generations of women doctors, she would likewise inspire so many women dental professionals.