Picture perfect

Medical illustrators play a vital role in our training and understanding

Philip Ferguson Jones

Medical Illustrator and Chairman of the Medical Artists’

Association of Great Britain

If I had a pound for every time in my more than 20-year career someone said: “A medical illustrator, what’s that?” I would be a rich man. Once the question of what I do is answered, and I have explained why such artists are in existence, the next question I am frequently asked is how one ends up in such a profession and develops expertise in this field.

My answer to this last question is perhaps the easiest. Honestly, by pure chance. After graduating from Wrexham School of Art, like many others I struggled to forge a career in art. I painted murals in the old Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool and this led to a commission to paint a mural on the wall of a child’s bedroom. The child’s father, a surgeon, noted my ability to accurately illustrate facial anatomy from drawings I had done, and enquired if I would consider illustrating an article he was writing about a surgical procedure.

In 2001 my first medical commission for a surgical procedure titled The rhomboid flap in medial canthal reconstruction, came into being. On reading a description of the procedure I struggled to visualise what was happening. As I drew the shapes described on a piece of paper, everything became clear. From this moment, my career took a new direction. I was hooked and found myself, before long, in front of an interview panel applying to train with the Medical Artists’ Education Trust.

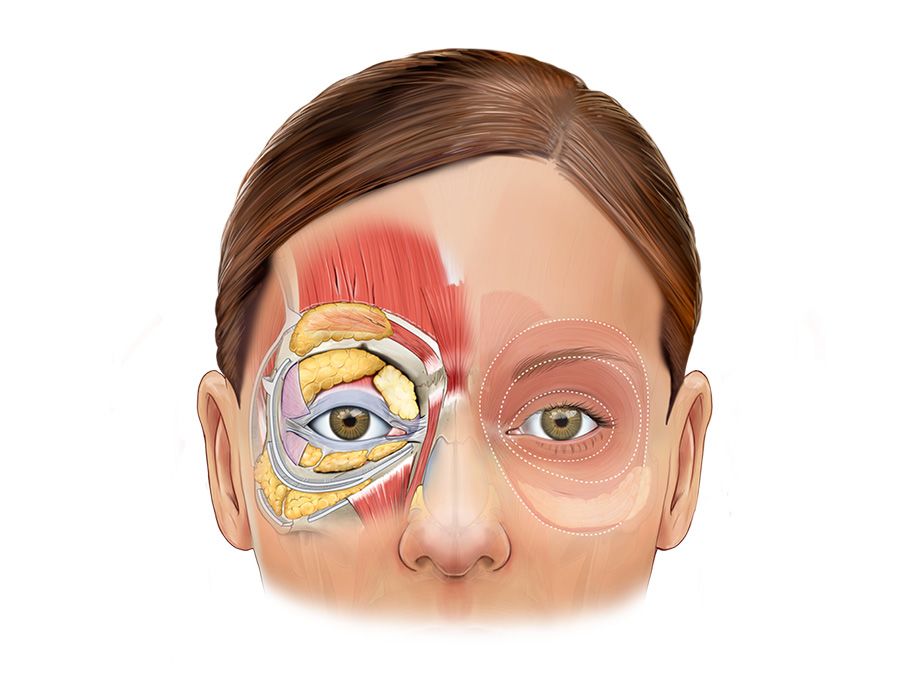

Orbital anatomy

Orbital anatomy

I became the illustrator of multiple editions of an ophthalmic surgery textbook; a children’s anatomical colouring book; patient information leaflets on cancer staging, catheters and stomas; and presentations and literature for pharma, detailing the mechanism of action of drugs.

Healthcare professionals, patients and their relatives, scientists, students in a range of different disciplines, those working in pharmaceutical and medical equipment companies all look frequently upon the work of medical illustrators.

Some may wonder where the pictures come from and who drew them. With only a handful of courses in the UK training skilled artists to the standard that is deemed a Professional Medical Artist, I feel proud to be part of this small and often unrecognised club.

Creating for COVID

The work of a medical illustrator varies with the time, situation and scientific developments. In 2020, when many reading this were learning rapidly about donning and doffing PPE, many of us were drawing the illustrations that appeared across hospital websites and in public places, showing people how to wash their hands, don and doff that PPE, and drawing the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself. Suddenly we all became very familiar with illustrating the anatomy of the top third of the face, the rest covered by a mask.

Throughout my career I have found myself frequently illustrating human anatomy of the head and neck. A chance meeting with a maxillofacial surgeon on the Isle of Mull led to the opportunity to study the anatomy of the human face in greater detail. Jeff Downie and his colleague Mark Devlin run courses at the RCSEd concentrating on giving further education in advanced facial anatomy and aesthetics. I have found myself for the past five years illustrating anatomical diagrams and teaching how to draw the face.

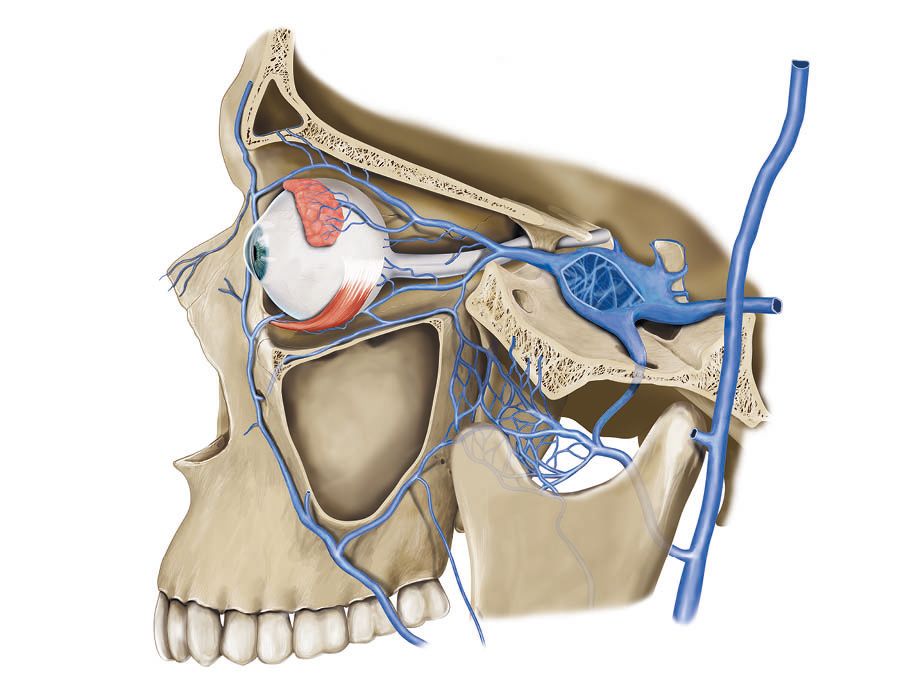

Illustration of venous draining of the orbit

Illustration of venous draining of the orbit

At an evening seminar delegates learn the Andrew Loomis illustration method, which helps one recreate the human head using geometry and thinking about the underlying structures. It proved to be an excellent way for delegates to relax after an intensive day of dissection while furthering anatomical understanding. There is an hour given for everyone to get to grips with a pencil and sketchpad, after which we see exciting results. Some surgeons claim not to have an artistic bone in their body, but after that hour they are surprised to discover they are more creative than they imagined.

Documentary practice

Determined to make the most of this environment, I have produced more than 50 digital illustrations depicting noninvasive surgical techniques with detailed anatomy. The documentary artist in me does not rest either. I have produced many sketches depicting surgeons and trainees at work – in this context documenting training through dissection and demonstration of anatomy, and its place in modern medical education, a practice that goes back as far as medicine itself.

The artist has always been an observer, sitting in the background, ideally unnoticed by the subjects they draw, capturing the activities of those around them in imagery. For me this has varied from drawing people on a train or a bar, to illustrations of my children as they grow. My most recent exploits featured doctors and nurses on the picket lines during the strikes.

The power of the image

This brings us to the hardest question to answer. In a world where every detail of everything can be captured and stored digitally forever, does illustration have a place? We live in a world filled with imagery. While you read through this magazine your eyes are drawn to the pictures before the text. If the image looks interesting, you find yourself reading the larger text. This is one sure way publications capture the attention of their audience.

An illustration is a drawing of a concept. The concept is a combination of the reality of the image or images that inspired the picture and imagination. The proportion of reality and imagination often depends on the purpose of the illustration.

Watercolour study

Watercolour study

Some medical and scientific illustrations, such as those that describe physiology, cell biology or the mechanism of action of a drug, require much more imagination to illustrate the concept, based on things largely unseen. Other medical illustrations, such as those focused on anatomy, require the highest level of accuracy, skill and knowledge. A surgical series, for example, must detail all the key features of the anatomy illustrated to proportion and in accurate relation to other structures. Our drawings are there as a reference and visual aid, guiding students in surgery and a range of other disciplines as they train.

In the dissection room, trainees experience the mess and the variability of human anatomy. They may reflect tissue to get a better understanding of, for example, the facial nerve. They may get to see a rare anomaly, an unexpected branch in an unexpected location. They may not find the facial nerve. They may if they are unlucky cut straight through it.

Our illustrations are a constant: a visual explanation, describing the expected patterns, the relationship, the location and the appearance, aiding memory and understanding. Can artificial intelligence replace such human skill? That’s a question for another day.