Improving outcomes

FDT Executive Committee Member Graeme

Bryce looks at the role of the webinar in shaping

healthcare organisations’ clinical practice

Graeme Bryce: Consultant in Restorative Dentistry and Specialist in Restorative

Dentistry and Endodontics, Defence Centre for Rehabilitative Dentistry; FDT Fellow

and FDT Executive Committee Member

The term ‘webinar’ first appeared in the 1980s, originating from the fusion of the words ‘web’ and ‘seminar’. Webinars were piloted for business purposes in the 1990s before being used for education in the 2010s as suitable hardware, software and broadband became widely available. The COVID-19 pandemic pushed learning online to the wider clinical audience, not just academia.

Clinical practice may be defined as the knowledge, skills and behaviours required to ensure the correct assessment, diagnosis, plan, treatment and review/discharge are attained. ‘Good’ clinical practice is not a discrete event, and evolves as evidence improves and societal expectations change. It is essential that organisations and practitioners engage with this progression to maintain their own professional relevance and to ensure optimised care pathways.

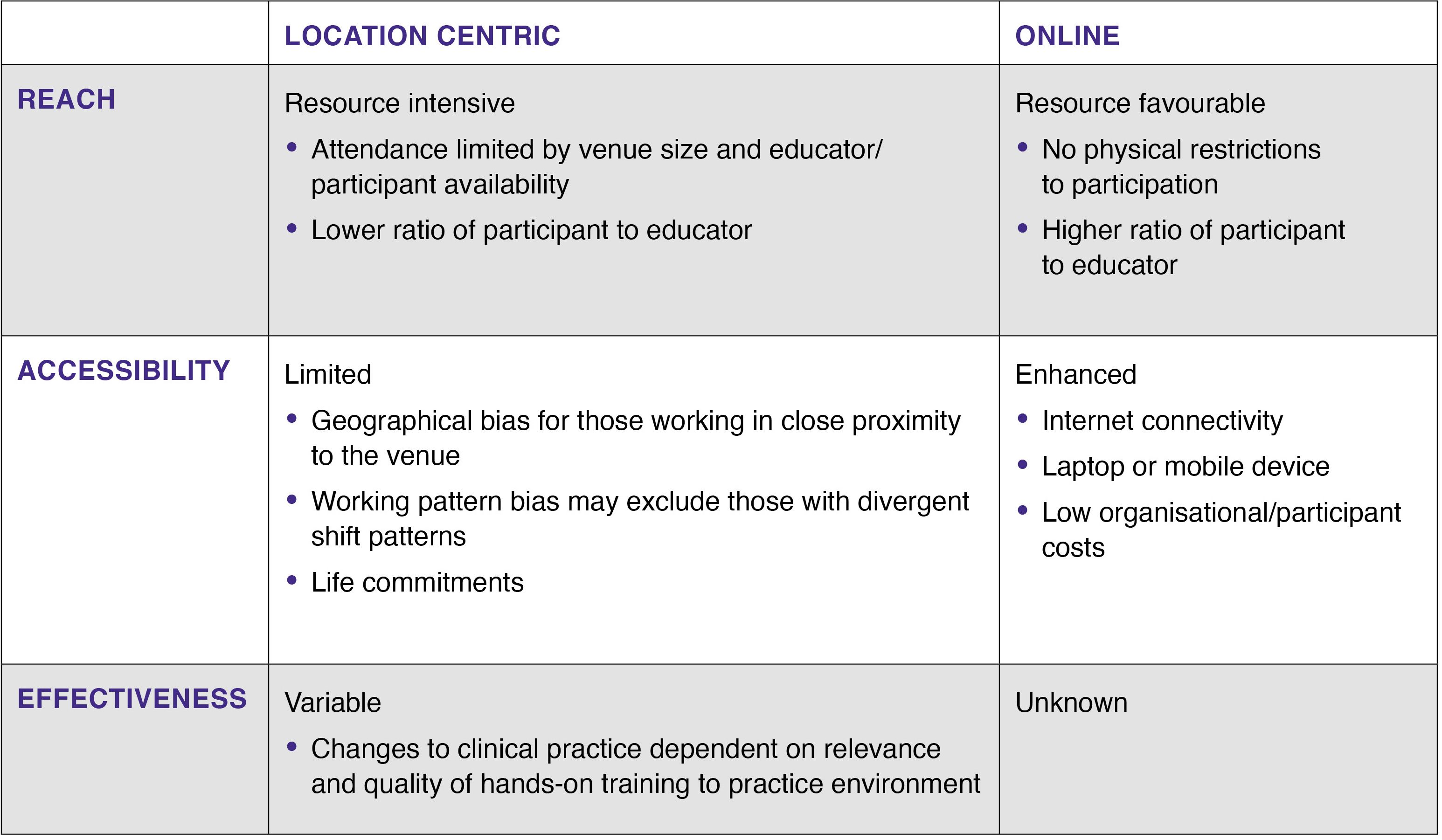

Historically, development of clinical education and practice was undertaken in person in physical locations limited by the size of venue and educator/participant ratios. Webinars offer clear training benefits with regards to reach and accessibility (Table 1). From the individual’s healthcare professional perspective, at its most basic the webinar offers easily accessible continued professional development (CPD), contributing to the process of maintaining professional registration.

Comparison of reach, accessibility and effectiveness of location-centric and online training

Comparison of reach, accessibility and effectiveness of location-centric and online training

Those with more defined aspirations may use webinars to develop either their own or their teams’ clinical practices to improve patient outcomes.

From an organisational perspective, webinars are a cost-effective tool that may reduce organisational risk by providing accessible training on essential safe working practices and improve communication with/between dispersed or shift-working teams.

Learning resource

Webinars have been extensively studied within secondary education environments1. It is unsurprising that webinars may be an effective teaching medium, given that students are mutually invested in their programme’s learning objectives and are generally supported with additional educational resources.

In contrast, clinical educators within mature healthcare organisations have an increased challenge of achieving universal engagement in webinars due to variation in the participants’ backgrounds, experiences and job role responsibilities.

The dental pillar of Defence Primary Healthcare (DPHC) employs military dental officers and civilian dentists to provide dental care to the UK Armed Forces, which are dispersed across both the UK and overseas environments. More complex restorative conditions are treated via the consultant-led Restorative Managed Clinical Network (RMCN).

An objective of the RMCN is to align practitioners to ‘best practice’ clinical care with the aspiration of standardising the quality of care provided across all DPHC dental centres. Historically, training was delivered via small group face-to-face clinical skills sessions. However, while generally receiving good feedback, these courses only reached a minority of clinicians and internal audit found limited effectiveness of such courses at realising sustained improvements in clinical practices.

Since 2018 DPHC has employed webinars to engage its clinical workforce as part of routine business. Although these webinars may present new clinical concepts and techniques, for patient safety reasons they do not advocate that clinicians work outwith their zones of competence. Rather, webinar content is largely targeted at standardising care and developing practices to improve clinical outcomes.

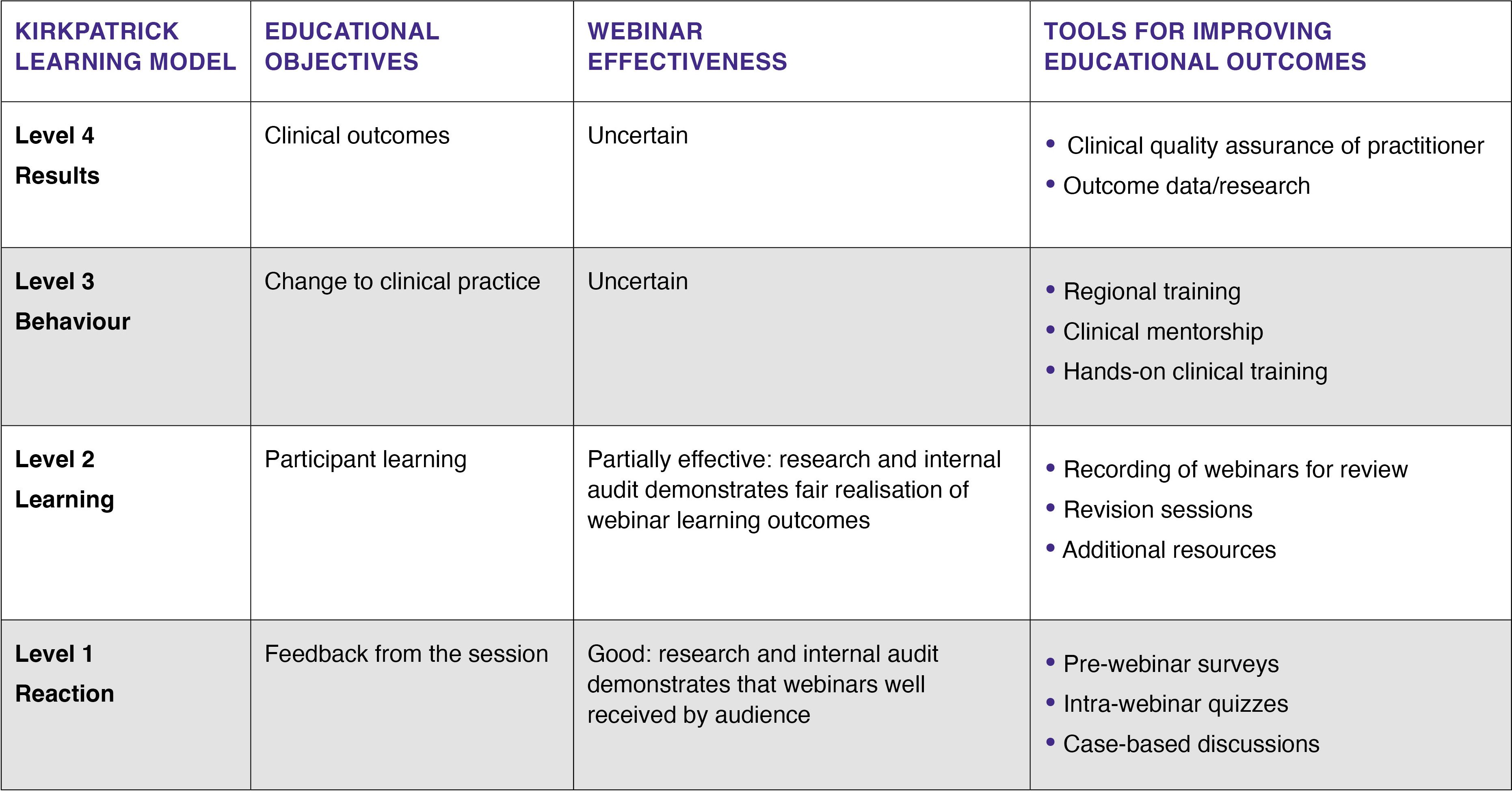

Evaluation of effectiveness of DPHC webinars using the Kirkpatrick Learning Model

Evaluation of effectiveness of DPHC webinars using the Kirkpatrick Learning Model

Supported approach

These webinars have been audited using a Kirkpatrick model2 (Table 2) and, similar to small group teaching sessions, the feedback (Level 1) on sessions has been positive. This feedback does not give true insight into audience engagement, and the proportion of the audience who have logged into the webinar but are paying little attention to the content may be unclear. In addition, engagement may be biased towards the motivated proportion of the workforce, with less reach to those who potentially are most in need of clinical development but abstain from attending.

Learning outcomes (Level 2) followed up at three months found that approximately 70% of participants could provide answers to questions that were aligned with the webinars’ objectives. These findings were dissimilar to external studies, which found better adoption of learning outcomes3. Attempts to improve audience engagement via interactive tools (Table 1) may improve participant experience but are unlikely to stimulate disinterested participants.

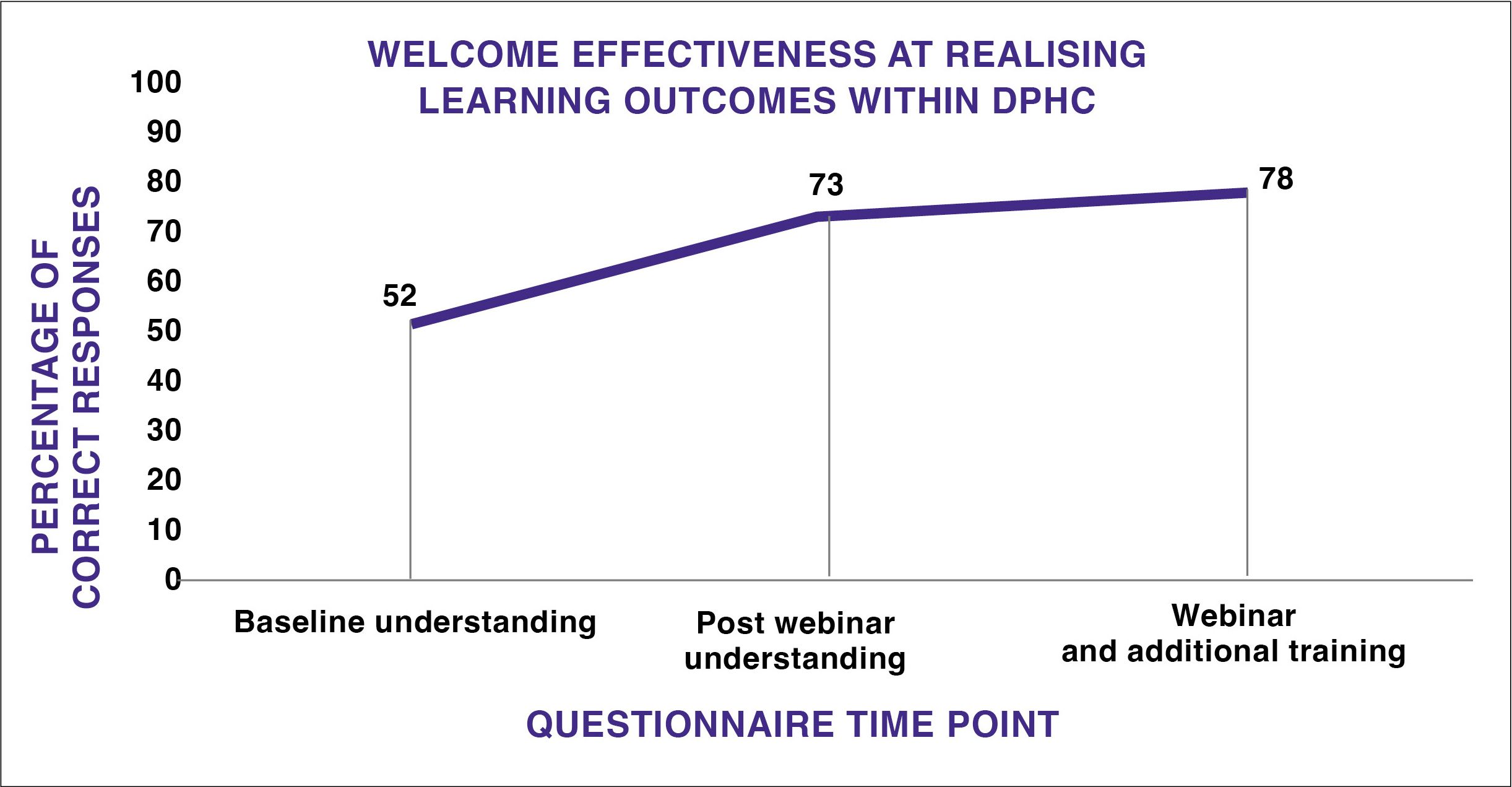

To develop pan-organisation clinical practices (Level 3), the RMCN supports webinar learning by producing additional resources that include instructional videos, reading lists and regional face-to-face sessions. This supported learning approach, underpinned by the webinar delivering the initial learning message, is demonstrating greater potential in developing clinical practices (Graph 1). In due course the aspiration would be to witness the materialisation of these practice developments via improved patient outcomes (Level 4).

For healthcare organisations, webinars can act as a platform to present clinical advancements, maintain CPD and reduce organisational risk.

Presently it remains unclear whether webinars can be used by organisations to predictably shape clinical practices and patient outcomes without support from additional training resources.

DPHC audit examining the effectiveness of webinars at realising learning outcomes within its clinical workforce

DPHC audit examining the effectiveness of webinars at realising learning outcomes within its clinical workforce

|

References 1.Gegenfurtner A, Ebner C. Webinars in higher education and professional training: 2.Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2006. 3.Berrett-Koehler Murphy B, Hoppe K, Gibbs C et al. Change in clinical practice in Australia: Impact of participation in MHPN webinars. J Integ Care 2018; 26(2): 101–108. |