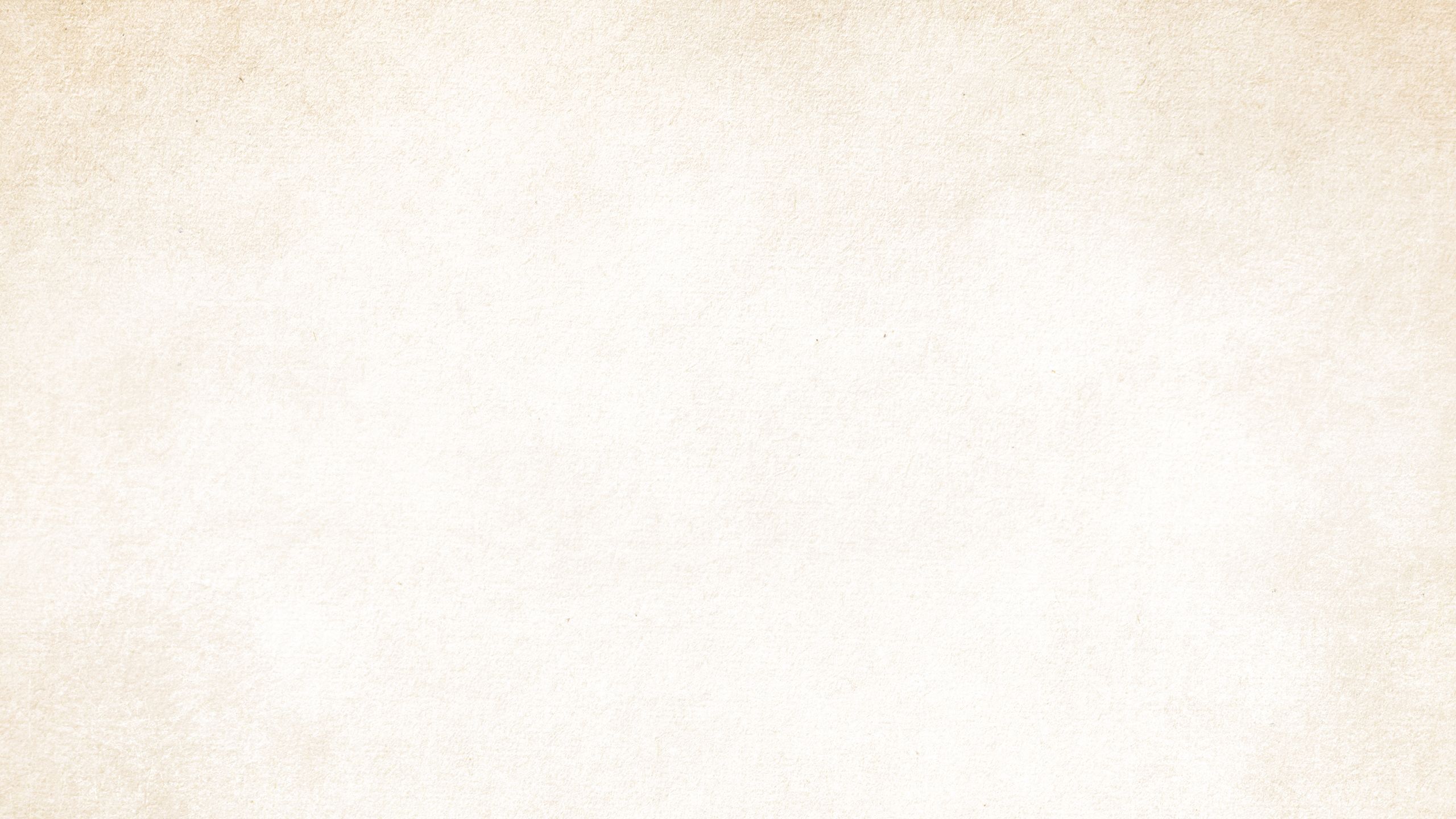

Charles Walker Cathcart

Covering the Field

Charles Walker Cathcart (1853–1932) practised surgery in two different centuries, served during the First World War, represented his country on the rugby field and aided Surgeons’ Hall Museums – first as a conservator and then a curator over a period of 32 years.

Born in Edinburgh in 1853, he would go on to receive his education, qualify, practise and raise his family in the city of his birth. Throughout his life he had success in many different fields, including surgery, surgical pathology, teaching and surgical publication.

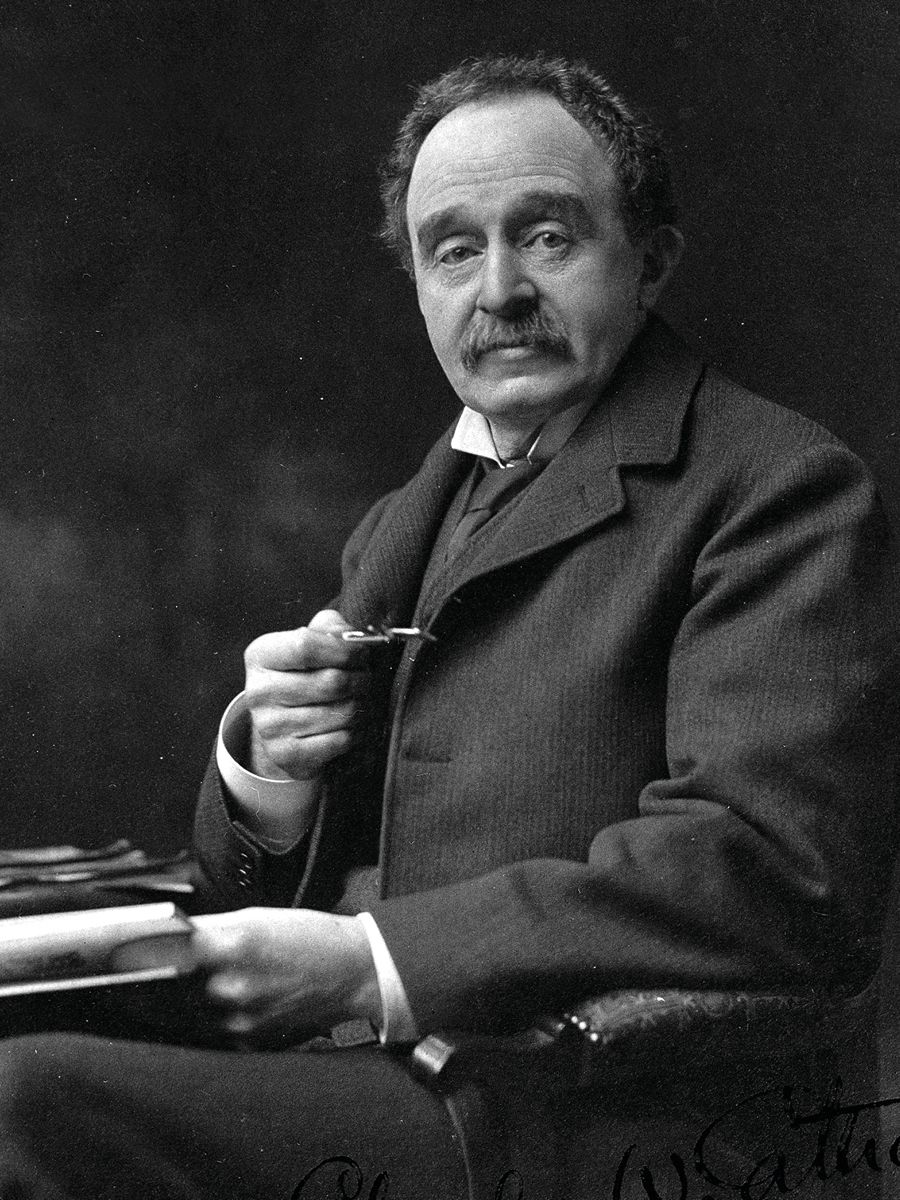

In this team photo dated 1872, Cathcart is pictured first on the left in the front row. Photo courtesy of Scottish Rugby

In this team photo dated 1872, Cathcart is pictured first on the left in the front row. Photo courtesy of Scottish Rugby

The playing fields

One of Cathcart’s earliest accomplishments was on the rugby field, representing his country at test level for four years. He made his debut against England at the Kennington Oval in London on 5 February 1872. During this game he scored a drop goal, but sadly Scotland were defeated.

Rugby was still in its early years, with the Scottish Rugby Union not formed until 1873, making it the second oldest organisation of its kind. Interestingly, in those days a try was only awarded if the conversion was successful.

Cathcart attended Loretto School in Musselburgh, which was one of the first schools in Scotland to create a rugby team. He was captain of this team and later played for the University of Edinburgh, as well as Edinburgh District.

In fact, he took part in another historical match, the first game of the Inter-City Derby, later known as the 1872 Cup, which is a fixture still played today between the professional teams of Edinburgh and Glasgow Warriors.

On 23 November 1872 the first inter-city game was played between Glasgow and Edinburgh at Burbank, Glasgow. Cathcart, while a student, was one of the forwards selected, playing at number 3 for Edinburgh. The game was a victory for Edinburgh with The Scotsman reporting on 25 November: “Good play was expected, nor were the spectators disappointed. Notwithstanding miserable weather, the match was played out in a truly splendid manner.”

The first ever international rugby match was held in Edinburgh at the historic Edinburgh Academicals ground at Raeburn Place on 27 March 1871. The challenge was issued by Scotland the previous December to the English clubs for a 20-a-side game, Scotland vs England.

This first encounter saw a victory for the Scottish team although, at the previously mentioned return match at the Kennington Oval in London in 1872, England were the victors. In 1873, Cathcart represented his country in the newly formed national team, which drew 0-0 against England.

In 1883 that competition became part of the annual Home Nations Championship, featuring England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. With the inclusion of France and Italy, the championship is now known as the Six Nations.

Craigleith Bowl presented to the 2nd Scottish General Hospital, the surgical units of which Cathcart organised

Craigleith Bowl presented to the 2nd Scottish General Hospital, the surgical units of which Cathcart organised

Cathcart’s last appearance for Scotland was against England on 6 March 1876, again at the Oval, which England won. This was also the last time 20 players would partake in a game of rugby for Scotland. Later that year a team of 15 became the standard and the rules were changed to allow a try to be counted even if the conversion was not successful. Cathcart’s rugby career concluded at the start of his medical career.

In the theatre

Cathcart studied arts at the University of Edinburgh, graduating in 1873 before studying medicine and qualifying MB, CM at Edinburgh in 1878. The same year he became resident surgeon with Professor Thomas Annandale at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, alongside Francis M Caird. In 1879 Cathcart took the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and, in 1880, became an RCSEd Fellow.

In a varied career he took on the management of the anatomy department at Surgeons’ Hall before going on to lecture on surgery at the Extra Mural School of Medicine in 1885. Eight years later, in recognition of his commitment to the College, including as lecturer and as conservator to the museum, he was awarded the last Liston Victoria Jubilee prize. Meanwhile, his surgical career went from strength to strength: he was appointed assistant surgeon to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary in 1884, surgeon in 1901 and consulting surgeon in 1918.

He had a considerable reputation as a teacher and his contribution to teaching was enhanced by two publications. He and his colleague Professor Caird published A Surgical Handbook: For the Use of Students, Practitioners, House-Surgeons, and Dressers in 1891. This book went through 20 editions and became a steady reference for generations of students. With his colleague J N Jackson Hartley he published his second book in 1928, Requisites and Methods in Surgery: For the Use of Students, House Surgeons and General Practitioners. This 476-page volume brought his earlier surgical handbook up to date and included more than 240 illustrations.

"He had a reputation as a teacher and his contribution to teaching was enhanced by two publications"

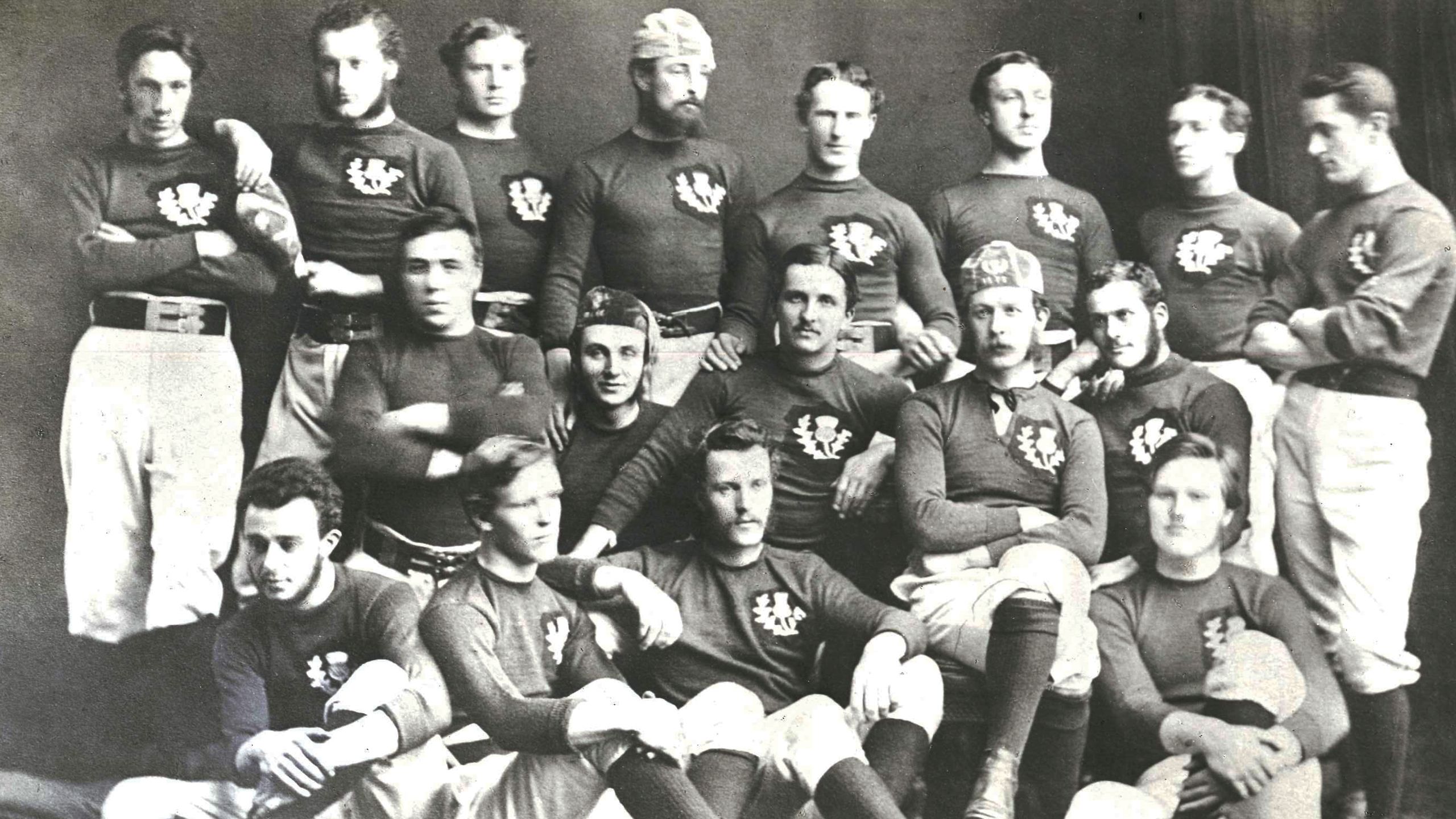

Cathcart (centre) with other medical staff

Cathcart (centre) with other medical staff

At the museum

Cathcart joined the prestigious list of Fellows involved with the College museum in 1887, holding the role of conservator for 13 years. In doing so, he joined the ranks of renowned conservators, such as Robert Knox, William MacGillivray, John Goodsir and Henry Wade. On retirement from the conservator post, he became curator and held this position for over 30 years until six months before his death in 1932.

As conservator he oversaw significant modernisation of the museum. At that time, it was primarily designed for and utilised by surgeons and surgical trainees. Cathcart viewed the museum as being for “instruction and demonstration” and set about a complete redisplay of the collections to make it more useful to modern teachings of pathology and surgery. This redisplay also enabled the completion of a new museum catalogue to complement study, with the museum shelves arranged to correspond to the catalogue entries.

Cathcart wrote: “Formerly… spirit preparations were place in one part of the museum, dried preparations in another… Now, they are all classed together in the catalogue when they belong to the same or similar specimens. In many cases published drawings of patients from who [sic] the specimens were taken have been copied… and placed beside the specimens they illustrate.”

The new catalogues enabled an update on descriptions of all specimens, including histopathology, where possible, and were published from 1893 to 1903. While preparing this catalogue, Cathcart invented a number and alphabetical classification system for pathology. This system came too late for inclusion in his catalogue, but he published his classification model and, in 1929, another conservator, David M Greig, used the system in a later museum catalogue.

Cathcart also catalogued over 1,000 new specimens and set up a museum laboratory, having decided that all museum collections should be examined microscopically and recorded. The laboratory undertook this work by cutting sections from specimens and using a microtome to slice the sections and place between glass for viewing under a microscope.

He also invented a ‘freezing microtome’, which froze small sections, and this offered a cleaner cut for viewing. This microtome now resides in the museum collection alongside a significant contribution of Cathcart’s specimens, casts and instruments.

Cathcart became chairman of the curators of the museum in 1900 and his influence can be seen throughout his chairmanship. The curators were established in 1804 to “form a Committee for the management of the museum, and who shall see that everything be duly taken care of”. The conservator’s role changed over the years and the last conservator was perhaps more in line with the role of a modern-day curator than a traditional conservator.

The title of curator still lives on at the College, although it is now a much more hands-on position, with management of the collections playing a key role.

Today, the museum also has a human remains conservator and this role, despite changes, still has much in common with the traditional conservator, with the responsibility of preserving and caring for the human remains collections.

"Perhaps his biggest contribution to the war effort were his ideas for products for surgical dressings"

Field of war

Cathcart was given a commission in the Territorial Force as Lieutenant Colonel à la suite in 1908. In the First World War he organised the surgical units of the 2nd Scottish General Hospital before serving as chief surgeon at the Military Hospital in Bangor until 1919. At the end of the war he became surgeon to Edenhall Hospital in Musselburgh, which housed limbless soldiers. For his war service he received an CBE in 1919.

A gas mask designed by Cathcart for the First World War trenches, which likely influenced the official models

A gas mask designed by Cathcart for the First World War trenches, which likely influenced the official models

In the museum collection we have examples of two other significant contributions Cathcart made to the war effort. First, in early 1914, he designed a gas mask for use in the trenches. The pattern was submitted to the War Office and, although not officially adopted, it possibly influenced the designs that were under study.

Perhaps his biggest contribution to the war effort were his ideas for useful, cheap and available products for absorbent surgical dressings. In 1914, Cathcart published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) the idea of using pinewood sawdust wrapped in mesh as a surgical absorbent dressing, which was favourably received.

In July 1925, in another article in the BMJ, he made a further suggestion of using sphagnum moss, instead of the costly and hard-to-acquire absorbent cotton wool, which was most commonly used by British surgeons. Quoting from an article he and Professor I Bayley Balfour had published in The Scotsman in 1914 he wrote: “On all our mountains and moors sphagnum is found in patches of varying extent, small or large. Its resilient perforated cells fit it admirably, and, indeed, suggest its superiority to cottonwool in absorptive capacity. We owe the introduction of sphagnums moss as a surgical dressing to Germany, where it has been established for this purpose for many years. Fas est et ab hoste doceri.”

This Latin phrase means ‘it is right to be taught even by the enemy’. The practice had been well established in Germany for around 30 years prior to the war and numerous articles existed in German about the abilities of the moss in surgical dressings.

In 1916 the War Office gave permission to use sphagnum moss and Cathcart then organised its collection in Scotland. By the Second World War there were moss collection stations throughout the country. His collection model would go on to influence collection drives in the rest of the UK and later America. It is estimated that more than one million moss dressings were used on the front each month during 1918.

The war sadly cost Cathcart dearly; his son was killed in action during the Mesopotamian campaign in 1916.

To conclude, I shall use the words from Cathcart’s obituary by those who knew and worked with him: “Mr Cathcart was respected by all who knew him as an excellent surgeon. His work was characterised by care, forethought, and meticulous attention to details. His conscientiousness and his rigid adherence to what he conceived to be his duty, even in circumstances which might prove to be unpleasant, were proverbial.”