Truth and compassion

David Alderson: Consultant ENT Surgeon, Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust

In a much viewed TED talk, Leilani Schweitzer describes her feelings when the nurse caring for her son went out of her way to look after her needs too: “I was so grateful for the prospect of silence and sleep.”

Seeing the effect of the constant, intrusive alarms on the exhausted mother, the nurse took the time to mute the monitor at his bedside. Tragically, the compassionate nurse had done so much more. She had managed to achieve what the manufacturers thought no one ever would: she had disabled all the alarms, everywhere.

“So when Gabriel’s heart stopped beating there was no sound. Just quiet. Nothing woke me until several minutes had passed and I was being jerked awake, and the room filled with people and panic,” remembers Schweitzer. She talks very movingly about the impact of that mistake on Gabriel and the repercussions for herself: “The next hours were awful: my sweet boy had become a corpse hooked to machines. I sat next to him, begging him to come back to me.”

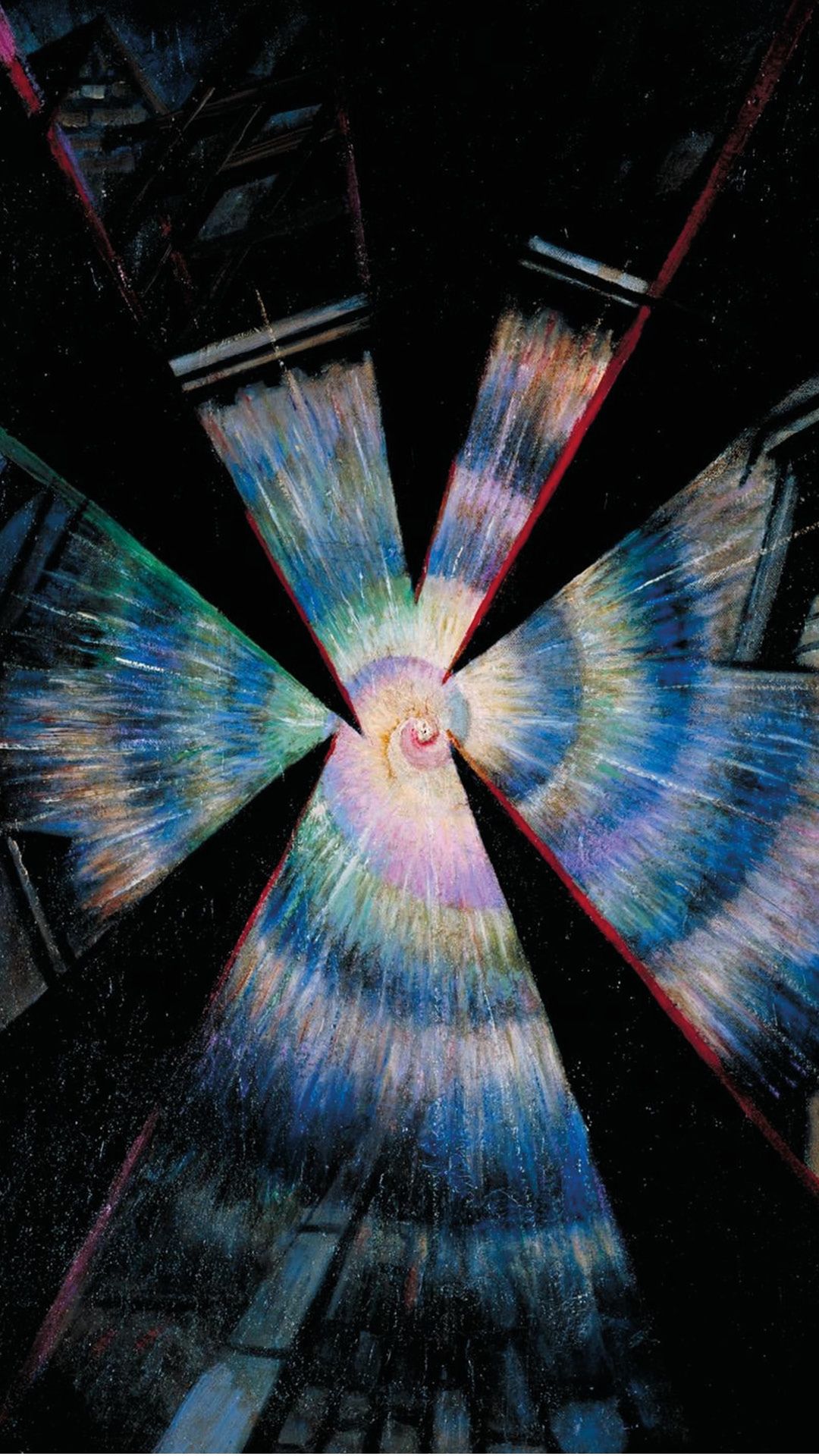

Bursting Shell (1915) by Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

Bursting Shell (1915) by Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

When I stand in front of Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson’s 1915 painting Bursting Shell at Tate Britain, I feel too that gut-wrenching sense of reality coming apart at the seams. But I recognise it not from having been on the receiving end of a serious mistake, but from making those mistakes.

Mistakes in medicine can be life-changing, lifelong and life-shortening – for everyone involved. Their dismaying frequency has been widely publicised over the last 20 years. Preventing them and mitigating their effects are now integral to all healthcare systems; learning lessons and improving systems have become fundamental responses to error.

And yet there remains a marked absence of nuanced discussion about the true nature of the practice of medicine by flawed human beings. In the mainstream media doctors and nurses must be superheroes or angels, or else they must be evil villains. When things go wrong patients and their families are portrayed as victims of abuse and healthcare professionals are the heartless perpetrators.

Tragic consequences

Schweitzer quickly recognised the fallacy of this caricature. She talks with great insight about the effects the incident had on the staff who looked after Gabriel.

“The day after he died, Gabriel’s nurse left that hospital for good. And one of the [surgeons] who took care of Gabriel later quit practising medicine altogether. All of their expertise and wisdom and experience is no longer helping children. That is another tragedy,” she says.

The term ‘second victim’ has been used by some authors, but it alienates many patients and family members, even those like Schweitzer who recognise these terrible events deeply affect us all.

“We all should have been given ID bands and become patients that day,” she adds.

Dr Margaret Murphy lost her son Kevin to an administrative error: a failure to see and act on the result of a blood test (written on a Post-it note) cost him his life. She told me about a chance encounter with the doctor involved. When she introduced herself he literally ran away from her in great distress.

Murphy thinks that ‘shared abandonment’ better encapsulates the isolation and trauma that can affect us all, not only from the original mistake, but also from the subsequent events that act to destroy the healing relationship that ought to remain at the heart of enabling us to cope.

After Gabriel died Schweitzer encountered a culture of ‘deny and defend’.

“The local hospital ignored me. By going ... silent, they didn’t just humiliate me, they denied Gabriel his dignity. And … that wound is very far from healing,” she says.

“For an apology to be able to nurture ongoing relationships, for it to be real, it must acknowledge harm, accept responsibility and express regret”

The responses of those suffering as ‘second victims’ can so easily translate into ‘second trauma’ for the patient and relatives.

How can we start to bridge this chasm? Nancy Berlinger has looked deeply at the ethics of the situation. In After Harm2, she writes: “If we agree that everyone makes mistakes, we are required, as rational and moral beings, to think about what happens next.”

She believes truth telling within an ongoing relationship is the hinge on which all else hangs. She highlights the power of a narrative approach to disclosure, not as a ‘performative utterance’ in search of ‘cheap grace’, but according to the needs and timeframe of the individual.

Schweitzer again: “We want an honest, transparent explanation of what has happened. We want a full apology. And we want to know and see that changes have been made to ensure that what has happened to us never happens to anyone else.”

Berlinger writes that for an apology to be able to nurture ongoing relationships, for it to be real, it must acknowledge harm, accept responsibility and express regret and repentance (including symbolic or concrete reparations).

Schweitzer distils it down into truth and compassion: “The University Hospital didn’t hide behind legal manoeuvres and dismiss me … They investigated, they explained, took responsibility and apologised. Then they asked me what else they could do. It made all the difference.”

When I set out to develop ways to engage professionals and the general public in meaningful dialogue about these issues, I knew I needed to draw on the experiences and perspectives of both groups. In creating my verbatim play True Cut, Schweitzer allowed me to use her words alongside those of clinicians I interviewed. The emotional responses of audiences convinced me of the power of this approach.

I am currently working with the College to find ways to promote these conversations more widely. My novel, Cutting, explores these themes in more depth and again relies on Schweitzer’s words alongside the real-life experiences and reflections of clinicians.

Making a difference

I was privileged to share a stage with Murphy for the post-performance discussion of True Cut at the IHI/BMJ Safety Conference in Amsterdam. In the decades since Kevin’s death, she has worked tirelessly as a WHO ambassador, seeking a culture that promotes ongoing relationships and open discussion after mistakes, looking for the common ground in our shared abandonment. In 2021 University College Cork awarded her an honorary doctorate in recognition of the widespread impact of her work.

Schweitzer has worked closely with the hospital where Gabriel died, developing, implementing and then leading its Communication and Resolution programme, which nurtures ongoing relationships between harmed patients and hurting clinicians, promotes learning and seeks an open and transparent solution for any potential areas of contention.

“Now they encourage me to share my ideas. They seek out my opinions. And they value what I have learned from Gabriel dying. They give me the opportunity to help people and that makes his life bigger,” she adds.

Changing culture is never easy, but creating opportunities for open discussion and shared understanding can make a real difference.

“I know what I’m asking for is big. I want a culture change. Maybe I’m talking about a revolution. [But] we should do it, because eventually we all are going to need to wear one of those plastic ID bands. Eventually we all are going to need the good healing medicine of truth and compassion,” says Schweitzer.

|

References 1. Schweitzer L. bit.ly/Truthandcompassion (accessed 15 Aug 23). 2. Berlinger N. After Harm. JHU Press; 2009. |