“I turned my life as a surgeon into a novel”

Mhairi Collie, a Consultant Colorectal Surgeon in Edinburgh, tells Jennifer Leyden how she hopes her debut novel will help change outcomes for African women injured during childbirth

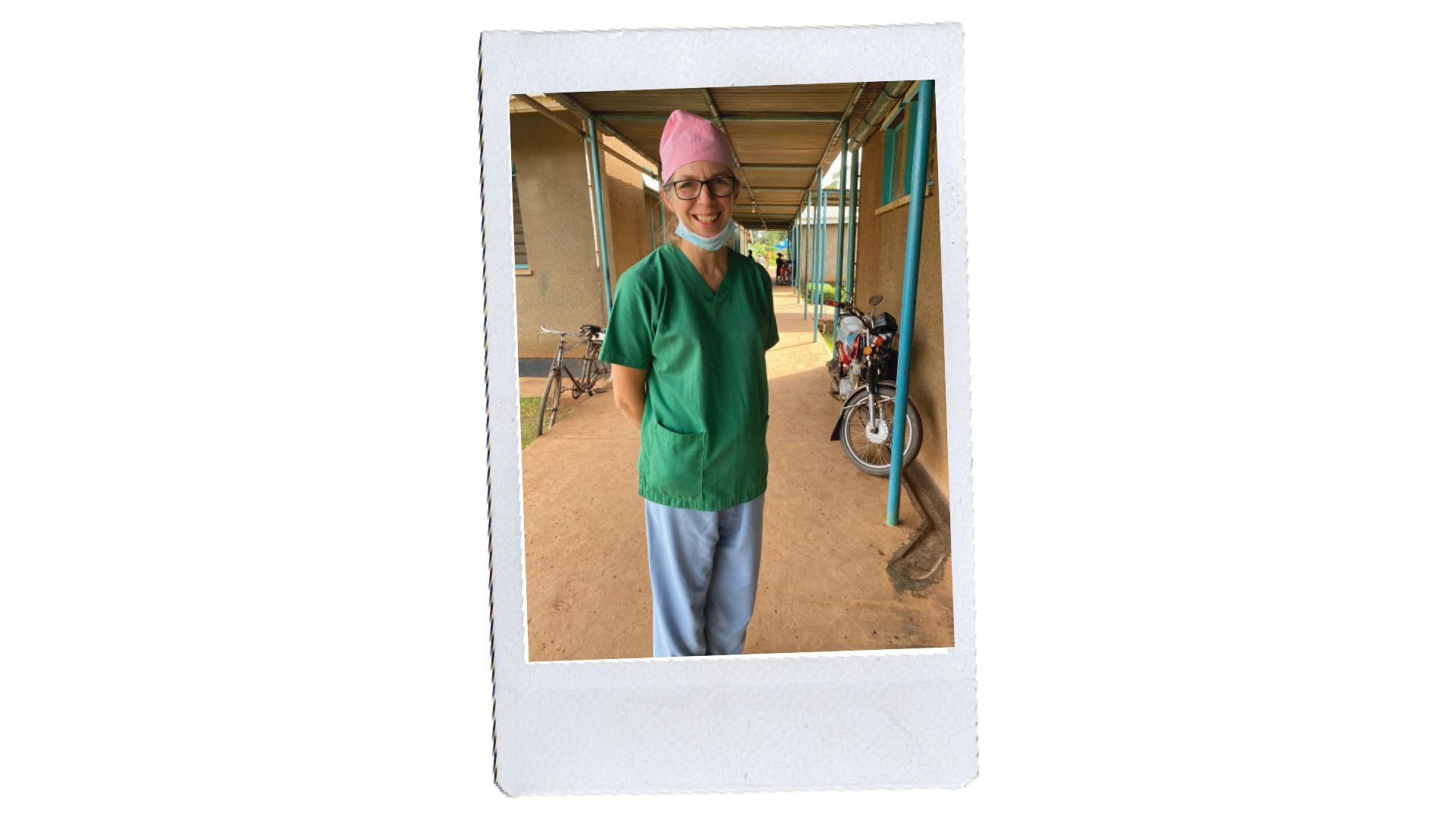

In 2001, Mhairi Collie worked for Médecins sans Frontières in Sri Lanka and Ethiopia, where she was thrown on to the front line, helping patients who had childbirth-related fistula or suffered injuries caused by being caught in landmine blasts.

She has since combined her colorectal practice with an ongoing involvement in treating obstetric fistula and, in 2003, co-founded the Uganda Childbirth Injury Fund. Over the past two decades, Collie has travelled regularly to Africa, not only to operate on women who have sustained childbirth injuries but also to help teach the vital skills local surgeons need to be able to treat them.

Now, her experiences have formed the backbone of Collie’s debut novel, a compelling and uplifting story called The Bright Fabric of Life. Set in Ethiopia and London, the book tells the tale of two young women who make a life-changing connection.

Sylvie has her dreams destroyed when a disastrous childbirth experience leaves her broken emotionally and physically, facing a lonely life of misery and rejection. Juliet is struggling with the many challenges that come with being a female surgeon in London. Unsure how to balance career, love and life – or how to manage her inner traumas – she escapes to work in Ethiopia.

Two women from different worlds are unexpectedly brought together, as Collie explains.

Tell us a little about the novel and what inspired you to write it.

I think there are two strands to this. First, I love reading, I love books and have always wanted to write. Second, I’ve been working with childbirth-injury patients in Africa for more than 20 years, hearing the same story again and again of how these young girls are left to give birth unaided in their village, and how they often lose their babies but so much more besides. Their injuries mean they are really discarded.

Usually, their partner or husband will take a new wife and they are left in pain, bereaved, incontinent and facing a very difficult life, disempowered and voiceless. I thought over the years of how I had never heard this story told in books or films, even though it is so common – the World Health Organization estimates that between one and two million women worldwide are in this situation, with more cases of obstetric fistula happening every day, every minute.

For us just to accept that so many women die or suffer lifelong injuries in childbirth seems so wrong. It should be a massive priority for governments and health organisations to address. I would like to try to bring this story forward.

Why did you think a work of fiction would work well to tell this particular story?

I think fiction is incredibly powerful – it personalises the sort of data I’ve just quoted and makes it human. I wanted to bring the story to an audience of people who could identify with the women. Sylvie is just like any girl here, with her dreams of love and motherhood. Also, I thought I would interweave a story of a female surgeon with some of the good and bad things that come with that, and let the two characters meet, potentially to help each other.

You share a lot of similarities with your character Juliet. Your commitment to women’s health is an inspiration but must come with witnessing distressing things. Would you say that writing this novel was a therapeutic experience for you?

Definitely. I think one of the hardest things about being a surgeon or a doctor is how you can be left wishing you had done something better, done something differently. It’s very hard to live with that.

You can’t be 100% perfect all the time but we tend to be our own worst critics. It’s tricky learning to manage that, to say: “Right, I’ve done the best I possibly can but this has happened and it’s not necessarily my fault”.

It was nice to talk about some of these difficult aspects of the job. We don’t always feel we can express our upset – we might have had a bad day at the office, but we are always very aware of our patients having a much worse time.

How do you hope your novel will affect its readers?

First, of course, I hope they will enjoy the story, appreciate the funny bits and, maybe, be moved by the sad bits. Second, I hope it might bust some taboos, particularly around incontinence. My clinics here in the UK are full of people who are so embarrassed about what’s wrong with them they hide it for years. I think it’s easy to feel defined by what’s wrong with you. That is something my African women experience, being defined by their injuries. It’s very hard to rise above that.

The last thing is about sharing our hopes and dreams, and our experiences of life, love and parenthood. I hope readers will see the women in the book as akin to them.

Where will the money raised by the book go?

All the profits will go to the charities on my website. We’ll ensure it goes to those who need it for treatment and prevention of childbirth injury. Fistula is a horrid outcome of childbirth, leaving a woman bereaved of her child, permanently incontinent and outcast. It is nearly always preventable if she can access help with delivery.

The Bright Fabric of Life is published by Maclean Dubois.

Read more