Setting goals' and improving feedback

Poppy Redman explains how the Surgical Education Checklist is helping trainee surgeons to maximise their learning under challenging circumstances

Surgical training has changed over time, but the operating theatre remains an important venue for the acquisition of key skills, particularly technical skills and decision-making1. Many factors have negatively impacted surgical training, including reduced working hours, increased patient and operation complexity and, more recently, the Covid-19 pandemic2–4. This has led to what Sadati et al. term “education in the shadow of treatment”5. The elevation of service provision over training as a priority needs to be addressed if the surgeons of tomorrow are to be adequately trained. Thus, we must focus on modifiable factors and make the most of every available training opportunity6.

Best practice

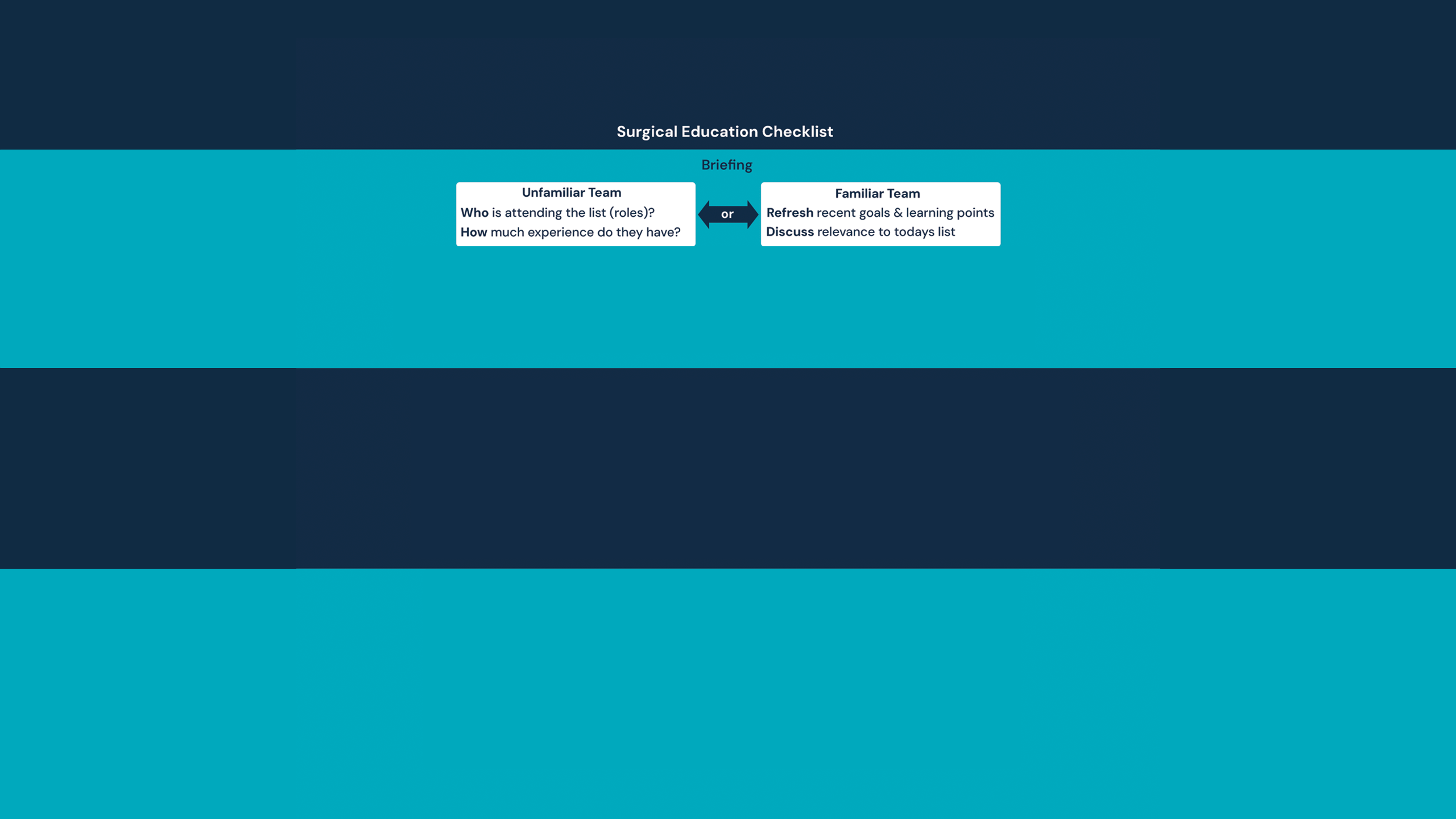

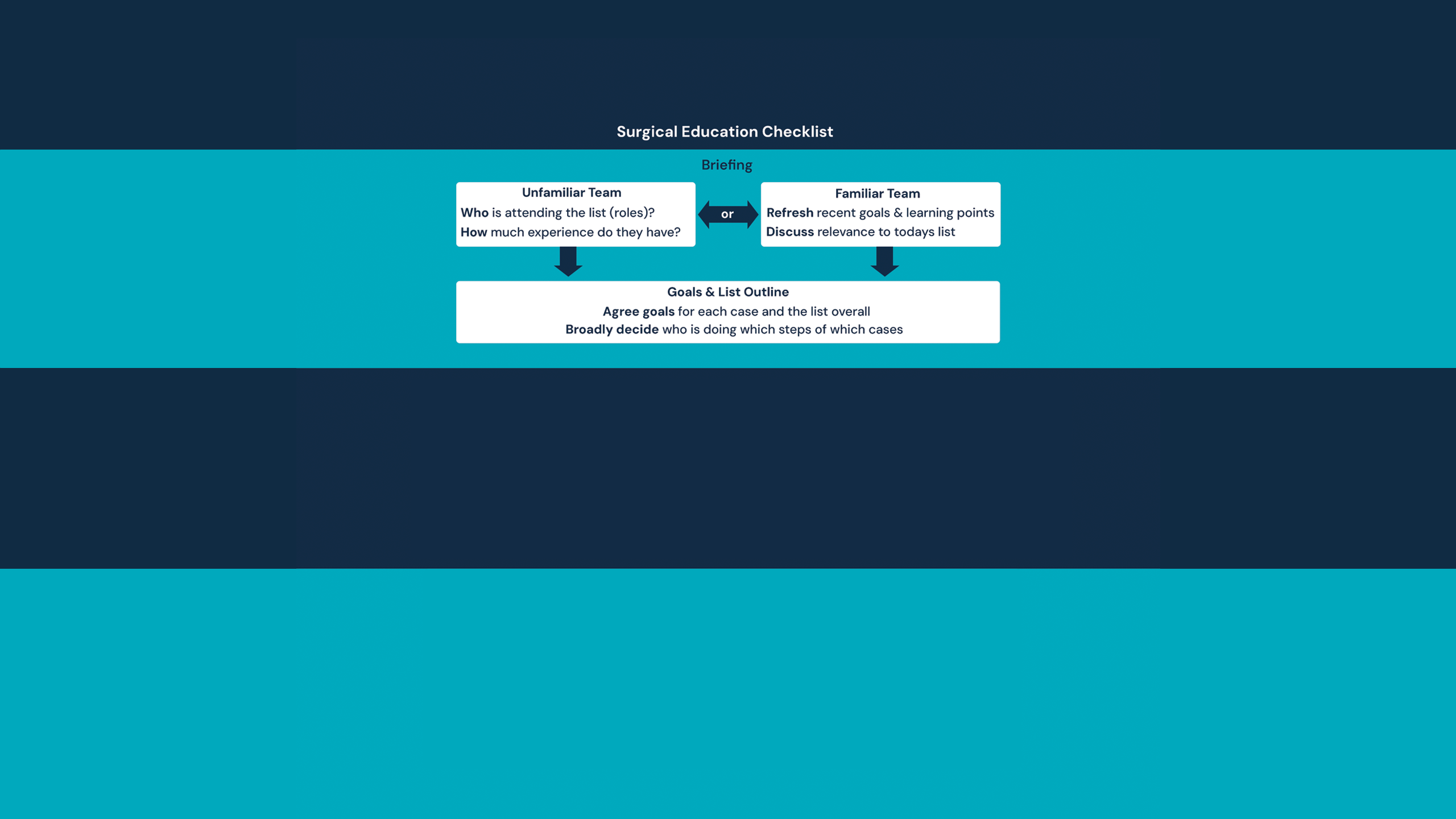

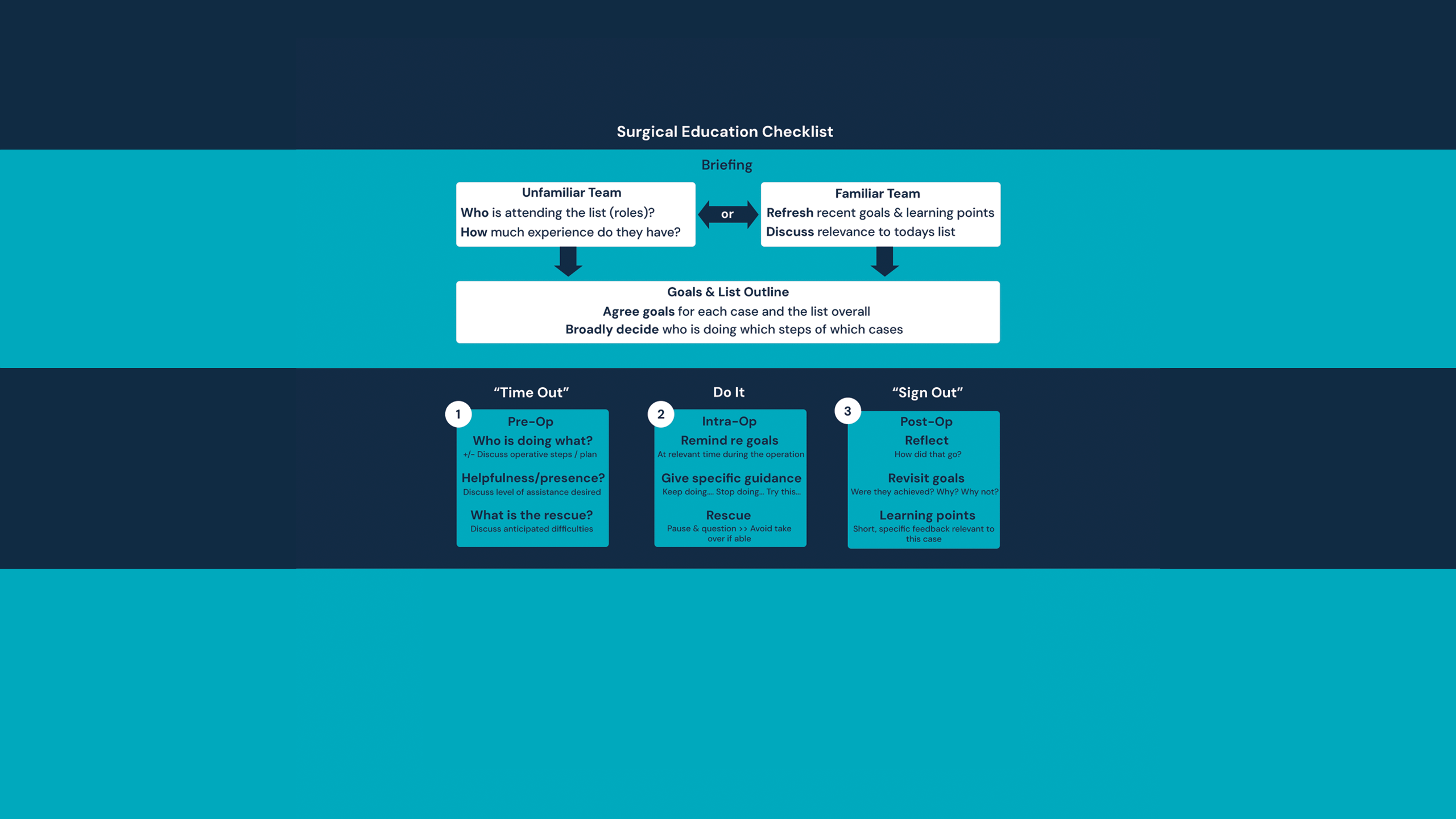

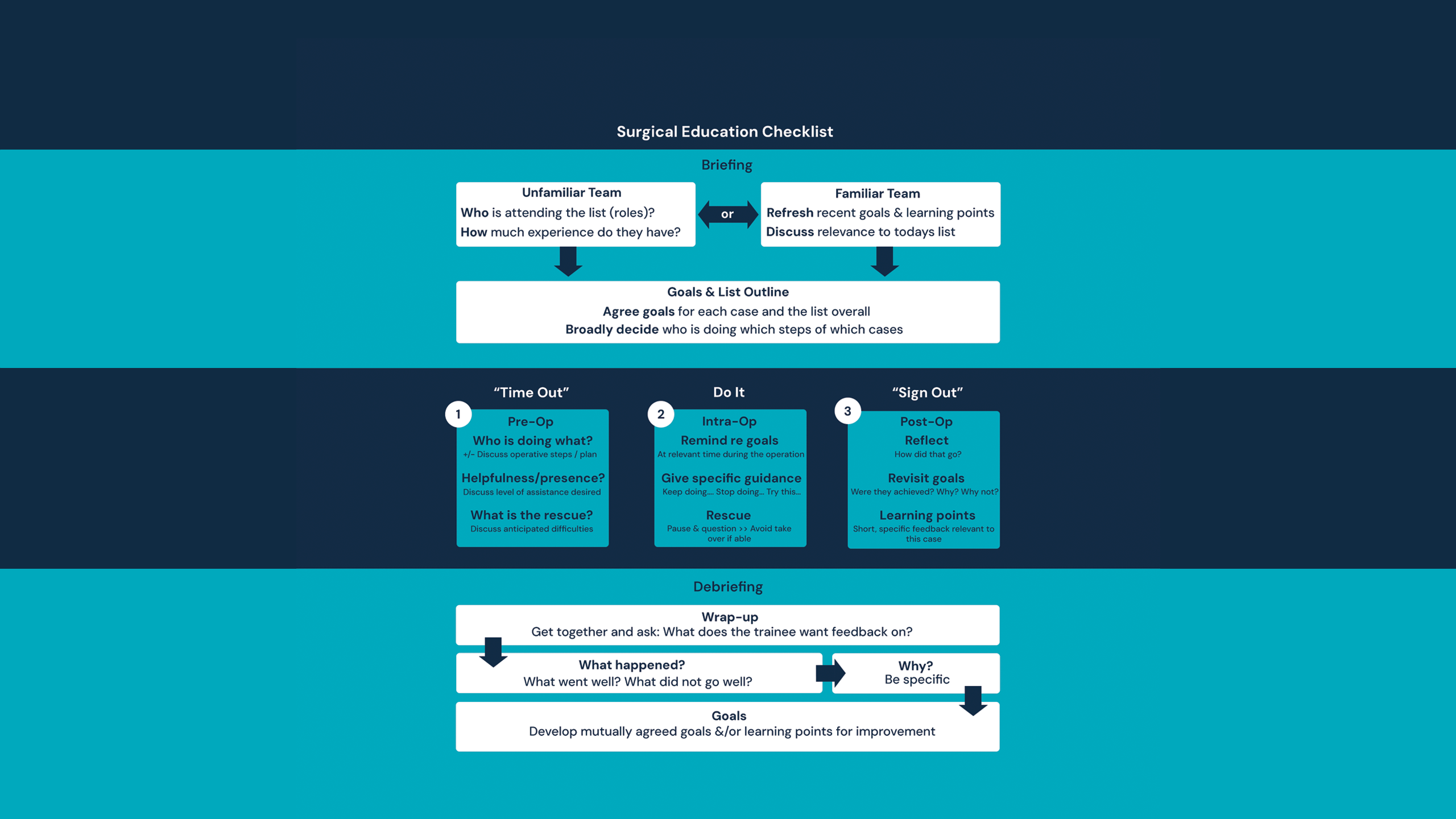

The Surgical Education Checklist (SEC) is an tool freely available to download at SurgEdChecklist.com. It is designed to be used as an adjunct to training in the operating theatre to improve the consistency and quality of education-focused discussions. Inspired by the success of the World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist, it amalgamates best practice in surgical education into an easy-to-use checklist that anyone can follow.

The SEC is designed to be used by any two (or more) people filling the roles of trainer and trainee, including consultants, fellows, registrars, core surgical trainees, house officers, and medical students. It can and should be used in both elective and emergency settings. Either trainer or trainee can initiate the use of the SEC.

Maximising learning

Within the literature, there is consensus that effective teaching in the operating theatre spans three phases: pre-operative, intra-operative and postoperative7,8. Before the start of an elective list, the SEC prompts discussion to establish who will be present and their experience level, which is especially important if working with an unfamiliar team.

When trying to maximise learning, it is valuable to ensure a trainee spends as much time as possible in their zone of proximal development, also known as the ‘growth zone’, where the most learning occurs9. This zone sits between the ‘comfort zone’, which is what a trainee can do independently, and the ‘panic zone’, which is beyond their capabilities. In the zone of proximal development, a trainee progresses their skill level in the presence of a more experienced trainer, who can provide feedback, ideally enabling a safe struggle10.

Discussing the trainee’s experience level and mutually agreeing goals beforehand fosters an environment where time spent in the zone of proximal development can be maximised. For example, if there is time pressure, the consultant could perform parts of the operation the trainee is comfortable with to give more time to the area they want to develop.

‘Time out’

Before each case, the SEC prompts confirmation of who is doing which steps of the operation. A trainee does not have to do the whole operation skin-to-skin to derive learning from the case. Using part-task training, where an operation is broken into steps, and only some of the steps are completed by the learner, allows the focus to be placed on where the maximum learning is11,12.

There are many levels of supervision and assistance13 in surgery, and a different level may be required for various steps of the operation. The level of supervision should be agreed upon beforehand to ensure that both trainer and trainee feel comfortable.

Discussing anticipated difficulties and what the rescue may be can be helpful. This discussion can improve the chances of the trainee successfully navigating a complexity or, if the trainer does have to take over, it can reduce the trainee’s feeling of failure, should that circumstance arise.

Explicit discussion and agreement of supervision and anticipated issues may aid in the complex but inherent negotiation of control14 between trainee and trainer.

Receiving feedback

If appropriate, feedback should be given during the operation that is both educational and also serves to advance the operation15. Remembering the zone of proximal development and a safe struggle is where maximum learning takes place; if the trainee is struggling, if it is safe to do so, it is preferable for the trainer to pause and question rather than take over. Prompts such as stop, start and continue16 can be used.

At the end of each case, it is useful to reflect on whether the goals for the case were achieved and, if not, why. Feedback is vital in surgical training17,18 but trainees are often dissatisfied with how much they receive4. A discordance between the perceptions of trainees and trainers as to how much feedback is given and received exists19 and is known as the ‘feedback disconnect’20.

Trainees frequently receive feedback during the operation. However, while performing a complex task, their cognitive load can easily be overwhelmed, resulting in difficulty transferring new learning from working memory into long-term memory21. Therefore, trainees may struggle to recall this feedback at a later stage.

Having a short, specific feedback discussion after every case can help consolidate the learning from the case and label the feedback as such to help address the issue of feedback disconnect20.

Debrief and feedback

If followed, the SEC establishes a routine-structured debrief and feedback conversation at the end of the operating list, which many advocate for6,22. By establishing feedback as routine, it is normalised and expected, making it easier to give constructive feedback and encourage positive feedback, both of which are required by the learner.

Focusing on creating goals is likely to improve the efficacy of feedback23 and encourages goal-orientation behaviours, which improves feedback-seeking behaviour24. Many believe feedback works best when it is sought by the learner17.

In order to maximise learning from pre-existing opportunities, we need to ensure trainees and trainers no longer subscribe to the dictum “no news is good news”25 when it comes to feedback.

The SEC is a low-tech, low-cost tool that combines much of the wisdom from the education literature into a checklist, which we have seen work in the operating theatre setting with the safety checklist26. The SEC is not about setting an expectation that the trainee should always be holding the knife. Rather, it is about establishing an open dialogue around learning goals; giving trainees a tool to empower them to advocate for their training and normalising routine feedback.

References

1. Iwaszkiewicz M, DaRosa DA, Risucci DA. Efforts to enhance operating room teaching. J. Surg Educ. 2008; 65(6): 436–40.

2. Hope C, Reilly J-J, Griffiths G, et al. The impact of Covid-19 on surgical training: a systematic review.

Tech Coloproctol. 2021: 25(5): 505–20.

3. Ranney SE, Bedrin NG, Roberts NK, et al. Maximizing learning in the operating room: residents’ perspectives.

J Surg Res. 2021; 263: 5–13.

4. Snyder RA, Tarpley MJ, Tarpley JL, et al. Teaching in the operating room: results of a national survey. J. Surg Educ. 2012; 69(5): 643–9.

5. Sadati L, Yazdani S, Heidarpoor P. Exploring the surgical residents’ experience of teaching and learning process in the operating room: a grounded theory study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021; 10(1): 176.

6. Lund J. Training during and after Covid-19. Bull R Coll Surg Engl. 2020; 102(S1): 10–13.

7. Timberlake MD, Mayo HG, Scott L, et al. What do we know about intraoperative teaching?: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2017; 266(2): 251–9.

8. Roberts NK, Williams RG, Kim MJ, et al. The briefing, intraoperative teaching, debriefing model for teaching in the operating room. J Am Coll Surg. 2009; 208(2): 299–303.

9. Vygotsky L. Thought and Language: MIT Press, Cambridge, MA; 1962.

10. Sadideen H, Kneebone R. Practical skills teaching in contemporary surgical education: how can educational theory be applied to promote effective learning?

Am J Surg. 2012; 204(3): 396–401.

11. Papachristos AJ, Loveday BPT, Nestel D. Learning in the operating theatre: a thematic analysis of opportunities lost and found. J Surg Educ. 2021; 78(4): 1227–35.

12. Spruit EN, Band GP, Hamming JF, et al. Optimal training design for procedural motor skills: a review and application to laparoscopic surgery. Psychol Res. 2014; 78: 878–91.

13. DaRosa DA, Zwischenberger JB, Meyerson SL, et al. A theory-based model for teaching and assessing residents in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2013;

70(1): 24–30.

14. Moulton C-A, Regehr G, Lingard L, et al. Operating from the other side of the table: control dynamics and the surgeon educator. J Am Coll Surg. 2010; 210(1): 79–86.

15. Roberts NK, Brenner MJ, Williams RG, et al. Capturing the teachable moment: a grounded theory study of verbal teaching interactions in the operating room. Surgery. 2012; 151(5): 643–50.

16. Hoon A, Oliver E, Szpakowska K, et al. Use of the ‘Stop, Start, Continue’ method is associated with the production of constructive qualitative feedback by students in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2015; 40(5): 755–67.

17. El Boghdady M, Alijani A. Feedback in surgical education. Surgeon. 2017; 15(2): 98–103.

18. Kieu V, Stroud L, Huang P, et al. The operating theatre as classroom: a qualitative study of learning and teaching surgical competencies. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2015; 28(1): 22–8.

19. Sendlhofer G, Mosbacher N, Karina L, et al. Implementation of a surgical safety checklist: interventions to optimize the process and hints to increase compliance. PLoS One. 2015; 10(2): e0116926.

20. Fulco F. Giving Feedback. YouTube™: VCU School of Medicine; 2014. Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYsobmPNs5g&t=186s

21. Howie EE, Dharanikota H, Gunn E, et al. Cognitive load management: an invaluable tool for safe and effective surgical training. J Surg Educ. 2023; 80(3): 311–22.

22. Ahmed M, Sevdalis N, Paige J, et al. Identifying best practice guidelines for debriefing in surgery: a tri-continental study. Am J Surg. 2012; 203(4): 523–9.

23. Hattie J. Influences on student learning. Inaugural Lecture. University of Auckland, 2 August 1999.

24. Teunissen PW, Bok HG. Believing is seeing: how people’s beliefs influence goals, emotions and behaviour. Med Educ. 2013; 47(11): 1064–72.

25. Bello RJ, Sarmiento S, Meyer ML, et al. Understanding surgical resident and fellow perspectives on their operative performance feedback needs: a qualitative study. J. Surg Educ. 2018; 75(6): 1498–503.

26. Bergs J, Hellings J, Cleemput I, et al. Systematic review and meta analysis of the effect of the WHO surgical safety checklist on postoperative complications. Brit J Surg. 2014; 101(3): 150–8.

Read more