Keeping up with the times: women and RCSEd Fellowship

Jacqueline Cahif follows the long and winding journey women had to take, from 1886 to 1920, to achieve an equal status in the College with their male counterparts

At a meeting in 1886, the President and his Council resolved “to admit Female Candidates to the Licence of the College” yet there was “no obligation to admit female Licentiates as Candidates for its Fellowship”. Female admission to Fellowship would take another 34 years. Having previously considered women’s access to the Licentiateship examination, it feels appropriate to now consider the College’s journey to electing its first female Fellow in 1920.

On the College’s historical attitude towards women, Helen Dingwall concludes that it “was probably no more (or less) misogynistic than any other institution at the time”. I disagree somewhat and suggest this is a generous interpretation that leans into the ‘they were of their time’ narrative. It does not fully capture a story that leaves the College in a less than favourable light, for several reasons. First, considered within the context of the surgical colleges in the United Kingdom and Ireland, we were the last to permit women admission to Fellowship (and not by just a couple of years). Second, we were the only surgical college to admit women reactively in response to legislation, with the decision effectively taken out of the College’s hands. Lastly, we have previously assumed the delay was because the issue never seriously arose, as evidenced by the College minutes. However, an under-explored collection of letterbooks sheds new light and offers a fresh perspective.

Agnes Savill (far left) with Scottish Women’s Hospital surgeons and doctors

Agnes Savill (far left) with Scottish Women’s Hospital surgeons and doctors

The first women

As early as 1885, the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland approved the admission of women to Fellowship and, in 1893, Emily Winifred Dickson became its first female Fellow, not only of that College but all surgical colleges. The Royal College of Surgeons of England polled its membership in 1908 and Eleanor Davies-Colley was elected in 1910 under the provisions of the Medical Act 1876 (women could not vote or hold office). With the legal precedence well established and after a ‘softening’ of attitudes, the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow followed suit in 1910, putting the issue to vote and Jamini Sen obtained Fellowship in 1912. And in 1920, Alice Mabel Headwards-Hunter became the first woman elected to the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

The First World War

Despite being able to graduate in medicine by the close of the 19th century, post-registerable qualifications were still mostly closed to women, as was the network of medical societies. This was a significant barrier to career progression, precluding women from senior or sought-after hospital roles and limiting most to general practice.

Surgical work was restricted to female-run hospitals for women and children, such as Edinburgh’s Bruntsfield Hospital, where Gertrude Herzfeld (our second female Fellow) spent much of her career. Yet only very minor surgery was performed, with more serious cases requiring a consultant from the Royal Infirmary. In Herzfeld’s words: “this state of affairs continued until just before the First World War”. The war radically changed the situation, affording female surgeons new professional opportunities to carry out the same complex operations as men. Herzfeld later reflected: “I spent the next five-and-a-half years gaining experience”, including in the post of Senior House Surgeon at Bolton Royal Infirmary. Women also gained advanced skills in military hospitals, such as those established by the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service. With the arrival of peace in 1918, surgical appointments became scarce again.

Fading history

In the archive, we hold a set of letterbooks comprising carbon copies of outgoing letters from the College. Sadly, these are in a sorry condition and many have faded ink and barely legible text, thus are a vastly under-exploited research resource. Nevertheless, with perseverance they provide a wealth of supplementary information not found in the minutes. The letters show that the question of women and the Fellowship arose more often than has been realised and, from the late-1880s, women began making frequent speculative applications.

In 1889, Edith Ellen Ward LRCSEd made enquiry, having that year passed the College’s Triple Qualification Diploma. The secretary responded with a short, rather abrupt, reply: “Ladies are not admitted to the Fellowship of this College.” Many letters are similarly brusque, although some adopt a softer tone. In 1891, Louise Cooke LRCSEd was informed the Fellowship was not open to her and “I am afraid [the Fellowship] will not be opened for many years to come. The matter was discussed … and it was unanimously resolved … the Fellowship should not be opened to female candidates.”

While the College not exactly inundated with requests, there was a steady stream of correspondence, which gathered pace from the early-1900s. Around this time, the College appeared sufficiently concerned and the thought of female voting influence consequent with Fellowship seemed a particularly intolerable prospect. In October 1903, the College secretary wrote to the Irish college: “There is at present a little agitation to have women admitted for the examination of Fellowship … I am asked to enquire what your College does in regard to the administrative powers of female Fellows.”

An interesting letter was sent in 1905 to Jessie McLaren MacGregor LRCSEd, one of the first women to qualify in medicine from Edinburgh University. She was informed the matter was going to be considered at a Council meeting, yet there is no minuted evidence this happened and she appears to have been ‘fobbed off’.

By 1916, and despite already proving their surgical competence in wartime, the College still had no appetite to admit women. A lady employed at the City of London Hospital was told there would be “no likelihood of a change”.

It has been fascinating to find that many women, who later became prolific in their field, were rejected from consideration. These include Agnes F. Savill, the first female graduate of St Andrews University, who pioneered radiography of gas gangrene. All told, the letters show that the College repeatedly disregarded the matter, ultimately dragging its heels until it was no longer able to do so legally.

Gertrude Herzfeld

Gertrude Herzfeld

Momentous legislation

It was not until December 1918 that the issue appeared in the minutes, when the President expressed his plan to “submit the question to the College in the coming year”. Pressure was mounting; that year a Parliamentary Act granted limited voting rights to women, and the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill was now before Parliament. This would be a momentous piece of legislation, ruling that women could no longer be barred by gender from entering professions or taking on important civic roles.

A sub-committee of Council members presented a report to Council on 16 December 1919. Interestingly, although the report advocated for female admission, which Council initially agreed to, its position then altered and it was decided the final outcome would be dictated by legislation: “no further actions be taken pending the disposal of the … Bill by Parliament”. Yet, when the Act did pass on 23 December, the College attempted to sidestep it as a private institution. It then solicited counsel opinion in February 1920. Hugh Pattison Macmillan KC fed back stark conclusions that the act applied to public and private bodies alike and therefore: “A woman cannot be refused admission as a Fellow, Licentiate or Diplomate on any grounds other than those on which a man can be refused admission. As regards the appointment of Office bearers, I am of opinion that a woman Fellow [should have] not only the right to vote in the appointment of Officer Bearers but also the right to hold office…”

His parting remark was unambiguous: “The [present] Laws of the College … are to cease to operate”. Accordingly, on 3 March 1920, the College “reconsidered the whole matter in light of the Law Agent’s advice”. Women would be admitted to the Fellowship with the same rights and privileges as men.

Why did the College resist?

The College’s key argument rested on semantics. It alleged that it would be ultra vires to make women eligible because the 1851 Royal Charter was created for male surgeons. However, the charter did not use gender pronouns, instead referring to “person” or “candidate”. Curiously, unlike the charter, the College Laws on the Fellowship did use male pronouns. However, those concerning the Ordinary Diploma – thus covering female Licentiates – also used male pronouns, thus a general term for both sexes. This puts a further cynical spin on the case because legally it would have been entirely practicable to admit women to Fellowship. More than 20 years earlier, Glasgow Fellows made similar arguments quoting their original charter. Kristin Hay suggests: “The emphasis placed on archaic gendered language shows the deep-rooted sexism in the faculty and the ways in which they sought to preserve their identity as exclusively male.”

Macmillan KC was explicit: “It is immaterial that the present Laws of the College refer solely to male sex” and, to avoid ambiguity, new RCSEd laws should conform “by altering their phraseology”.

This then was the outward rationale documented by the College. Other reasons for resistance can be inferred.

First, chauvinist institutional cultures and persisting separate spheres of ideology cannot be ignored. When she struggled to establish private practice, Herzfeld found: “Male practitioners were prejudiced against the idea of women doing major surgery”, also finding “marked discrimination” from patients. Second, Edinburgh was in an unusual position and the shadow of the tumultuous years surrounding the Surgeons’ Hall Riot probably still weighed heavy. Elevating women’s position above the Licentiateship was likely a step too far that made some members of the medical establishment nervous. Third, the nation was still in a state of grief in 1920. The war left men feeling uncertain about the future and the old way of doing things, no doubt, provided respite and feelings of normality (although this does not account for resistance before 1914). Finally, throughout its history as a private body, the College was often averse to interference by central (and local) government, perceiving it as an unwelcome encroachment on its own laws. This goes some way to explain why the College challenged the 1919 Act to the point of clutching at straws.

Operating theatre staff, Scottish Women’s Hospitals

Operating theatre staff, Scottish Women’s Hospitals

It would be unfair to conclude that the College was unequivocally hostile to female surgeons per se, far from it – the College actively encouraged women to apply for the Licentiateship. Yet, it actively sought to safeguard the male identity of what Dingwall regards “the historic core of the College’s functions”, that is, the Fellowship. Legislation eventually forced the College’s hand.

Having said that, if the Bill had not passed, I do not think the College would have delayed female admission much longer, and not only to keep up with the sister colleges. The war gave female surgeons the opportunity to prove their capabilities and expertise, and they should not be drained of agency in their attempts to obtain Fellowship. Almost as soon as qualifying with a diploma or degree, they sought the higher, more prestigious qualification, the ultimate recognition of surgical merit.

The College’s historical attitude towards women and the Fellowship sits in contrast to the inclusive reputation it acquired in subsequent decades, when medical schools in London and the US frequently criticised what they perceived to be an overly tolerant admissions policy for Triple Qualification Licentiate candidates from marginalised backgrounds.

Further reading

1. Dingwall H. A Famous and Flourishing Society: the History of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, 1505-2005. Edinburgh University Press, 2005, page 181.

2. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Admitting women [Internet]. 26 May 2021 [cited 9 Oct 2024]. Available from: https://heritageblog.rcpsg.ac.uk/2021/05/26/admitting-women/.

3. Dupree M and Crowther A. Medical Lives in the Age of Surgical Revolution. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

4. Herzfeld G. ‘Bruntsfield Hospital’, typescript draft paper, RCSEd Archive.

5. Unknown author. ‘Women and the Fellowship’, RCSEd Library and Archive.

6. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Gentlemen brethren and women [Internet]. 19 May 2021 [cited 9 Oct 2024]. Available from: https://heritageblog.rcpsg.ac.uk/ 2021/05/19/gentlemen-brethren-women/.

From mailings to magazines – how RCSEd reaches out to its membership

Robin Fixter-Paterson charts the development of how the College has kept in touch with members over the years

The methods by which the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh has communicated with its members have varied enormously over the five centuries of its existence. When the organisation was bound to a small geographic area, such conversations could be had verbally or, perhaps, through a short letter taken to your colleagues by an apprentice or indenture. Thankfully as the College has expanded, more sophisticated methods have been implemented.

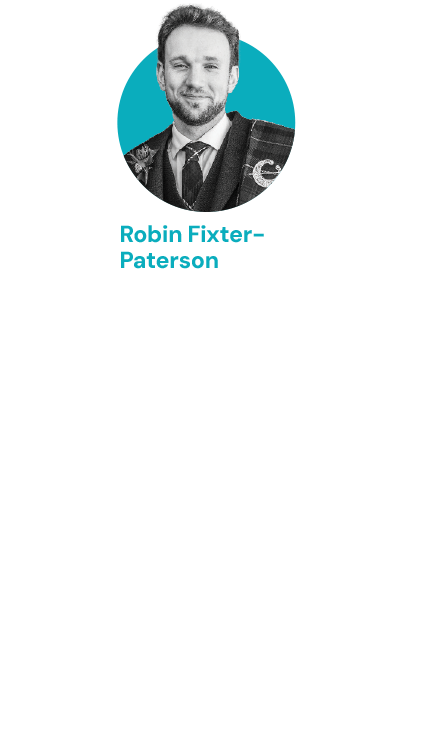

Through records preserved in our Library and Archive, letter-writing can be seen to be the primary method of communication used until at least the 1950s and, even then, usually for matters of business only. The College Billets, containing assembled syllabi and brief announcements, began to be sent to members by mail from 1959. Though informative, it retained a businesslike style and so did not represent much of a departure in tone from the formal journal, published since 1955.

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Syllabus for 1958-59

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Syllabus for 1958-59

However, this was a time of great expansion. From 1954, overseas Fellows were able to vote in Council elections and subsequent records of ballots cast showed that, within a decade, 25% of votes cast were from Fellows overseas. This change in the membership’s centre of gravity, alongside overseas exams from 1957, overseas meetings from 1976 and overseas ‘chapters’ of the College from 1978, meant more effort had to be made to keep members feeling included. In Council, Professors Francis Gillingham and Balasubramanian Ramamurthi pushed for a greater effort in communication, particularly as Fellows overseas wanted to be involved and to maintain close ties to Edinburgh.

With this in mind, the Newsletter began in 1981 as a self-described ‘new venture’. The two-sided A4 page in 1981 had developed into a vibrant, interpersonal publication by its end in 2001. Finally, members could see all the business information they had before, along with more personal fare. Historical pieces; motions in Council; upcoming social gatherings; application forms for courses; news from Edinburgh and reports from overseas members were combined, representing a dialogue the College had scarcely had with its members before.

A 1981 newsletter sent to members

A 1981 newsletter sent to members

The Newsletter set the precedent for Surgeons’ News. The first issue in 2002 recognised this, stating its desire to “initiate a proper two-way conversation between you out there and us back at HQ in Edinburgh” as well as to provide a lighter tone “for those who find they are saturated with news, political views and science…” This change in scope and a broadening of the College’s focus on communication beyond simple business has, arguably, been a great achievement and has been carried to all parts of the world where there are members of

our College.

In an era when inclusivity has taken centre stage in College values, the newest iteration of Surgeons’ News now takes up that mantle and leads the way in communication, which forms the bedrock of the College as an international entity.

References

1. RCSEd Minutes of Meeting of the President’s Council, 5 May 1954, page 3.

2. RCSEd Minutes of Meeting of the President’s Council, 16 October 1963, page 6.

3. RCSEd Minutes of Meeting of the President’s Council, 14 October 1970,

pages 93-4.

4. RCSEd Minutes of Meeting of the President’s Council, 14 May 1971, page 16.

5. Surgeons’ News 2002; 1(1): 1.

6. Ibid.

Read more