The historical role of women in humanitarian healthcare

College Archivist Jacqueline Cahif spotlights some of the women who have helped drive meaningful change in surgery

Women have always played a pivotal part in delivering humanitarian healthcare relief, including in regions affected by crisis, conflict or disaster, and in areas of poverty or where authorities or belief systems have marginalised women and girls, thereby reducing their access to healthcare. Today, female medical practitioners are celebrated for their humanitarian work with international agencies, such as Médecins Sans Frontières and the Red Cross. Licentiates and Fellows of this College have historically been instrumental in effecting meaningful change in humanitarian medicine – particularly in international contexts – by offering vital leadership and service. Some have gained widespread recognition, while others have received less attention.

Elsie Inglis LRCSEd and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals

One of the most remarkable groups of women to advance humanitarian medicine abroad in response to crisis was that associated with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH) for Foreign Service, established by the doctor, surgeon and suffragist Elsie Inglis. In 1892, Inglis obtained College Licentiateship after passing the Scottish Triple Qualification, and the subsequent record of her accomplishments are well documented, especially in advancing maternity and infant healthcare and welfare in Edinburgh. However, Inglis’ overseas wartime humanitarian work arguably represents the most pioneering aspect of her career.

When World War One broke out, Inglis approached the War Office with a proposal to establish all-female staffed medical units in support of the war effort. Her offer was dismissed with the remark: “My good lady, go home and sit still.” Undeterred, she persevered, and her proposal was accepted by the French Red Cross and the Serbian government, leading to the deployment of the first SWH units to Serbia and France shortly thereafter.

SWH staff worked as surgeons, doctors, radiographers, nurses and orderlies in stationary and mobile field hospitals in France, Greece, Serbia, Russia, Romania and Malta. The majority did so voluntarily, relinquishing comfortable middle-class lives to venture into unfamiliar and dangerous territory, often close to front lines where official military medical care was inadequate or inaccessible. Under pressing conditions, they undertook the urgent and demanding tasks of setting up operating theatres, X-ray facilities, clinics and wards, and provided essential medical and surgical services to wounded and sick soldiers, as well as supporting refugees. During 1915, several women were even captured by the Austro-German army while running a series of field hospitals, dressing stations and clinics in Serbia on the Balkan Front. Among those taken prisoner was Inglis, who was leading that specific unit. With assistance from American diplomats, the British authorities ultimately succeeded in negotiating their release.

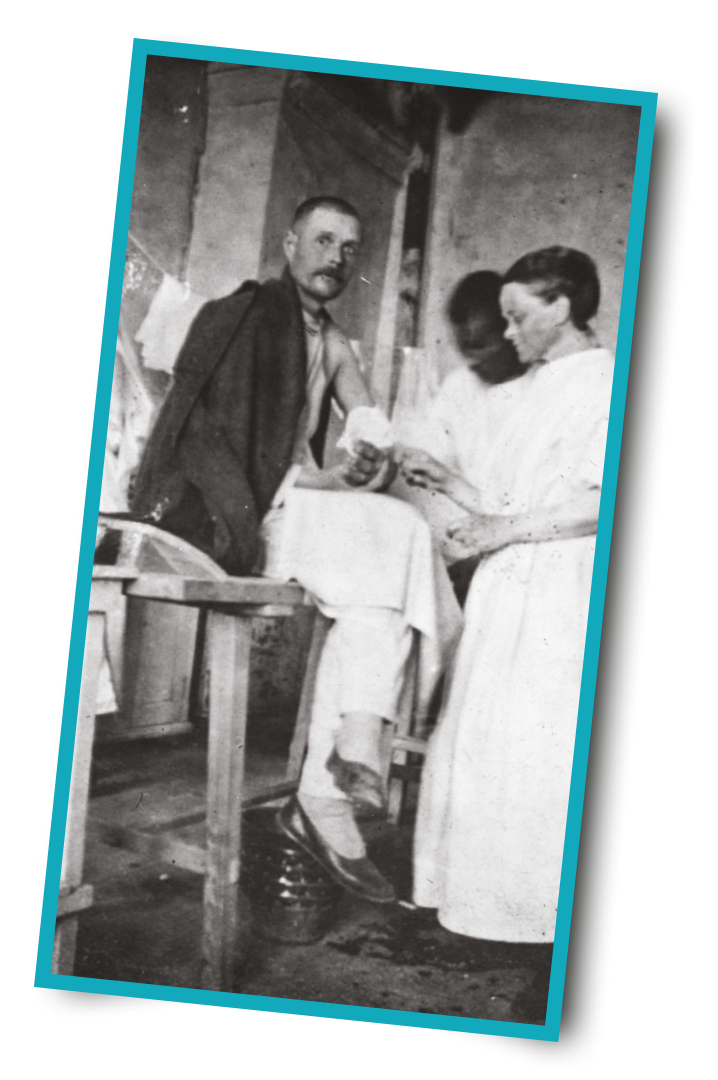

Elsie Inglis treats a patient

Elsie Inglis treats a patient

The scale of the SWH’s impact is demonstrated compellingly by the creation and operation of the stationary hospital at Royaumont, France. A team headed by gynaecologist Frances Ivens transformed a large, dirty and draughty 13th-century Cistercian abbey into a functioning military hospital, equipped with 100 beds, an operating theatre, laboratory and X-ray facilities. Royaumont remained in continuous operation for the duration of the war. Between 1915 and 1918, 10,861 patients were treated by the all-female staff. Staggeringly, this was achieved with only a 1.82% mortality rate. Royaumont doctors received recognition from the prestigious Pasteur Institute for their groundbreaking work in the treatment of gas gangrene through the use of X-rays and bacteriological diagnostic methods. By the close of the war, 1,500 women had served overseas with the SWH, delivering critical medical care to approximately 200,000 patients. Inglis and other hospital leaders demonstrated the capacity of women to effectively lead and manage a complex humanitarian initiative in wartime, disrupting prevailing gender norms of the time.

Medical missionaries and humanitarian healthcare

The evolution of modern humanitarian healthcare was strongly influenced by medical missionaries, and women made up a considerable proportion of those serving overseas with missionary organisations. Indeed, the inclusion of women in Christian missionary work from the late 19th century is regarded as a pivotal development in the advancement of women’s roles in medicine and surgery.

Female medical practitioners were highly sought-after in British colonial outposts, where cultural and religious practices prohibited male doctors from treating indigenous women. Yet the deployment of women in the missionary field could be negotiated only with access to medical qualifications. Therefore, it was not until the late 1880s that women could make advances as missionaries in a medical capacity.

In 1891, the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society adopted a sponsorship scheme to support the education of women as medical missionaries, enabling those with less financial means to enter medicine.

Yet despite being able to graduate in medicine by the late 19th century, post-registerable qualifications were still mostly closed to women. This was a significant barrier to career progression, ultimately precluding women from sought-after hospital roles and limiting most to general practice. Surgical work was restricted to the very few female-run hospitals for women and children, yet only very minor surgery was performed, with more serious cases requiring a male consultant. The opportunities presented by missionary medicine – including advanced surgery – were highly appealing in the face of discrimination from the male medical establishment, and were a major catalyst for women securing meaningful professional roles.

In remote regions of Africa, China, Syria, India and Palestine, women made important contributions in the development and expansion of medical missionary work. The Zenana ministry in India, in particular, appealed to British female doctors and surgeons, and many joined missionary societies in order to reach Indian women living in secluded or segregated spaces. By the turn of the 20th century, India had become the destination for more than one quarter of all British women who qualified in medicine.

Helen McMillan, FRCSEd

Some of the earliest female Licentiates and Fellows of this College joined the missionary movement, often co-founding or managing hospitals where they had the opportunity to develop and refine their surgical expertise. One woman who made a substantial contribution in this way was Helen McMillan, a surgeon who undertook Zenana work as a Church of Scotland medical missionary. In May 1921, she became the third woman to obtain RCSEd Fellowship (and was the first Scottish female Fellow). We are delighted to have recently acquired McMillan’s archive, a considerable collection of correspondence, photographs and artwork, kindly donated to the College by her family. This is a major acquisition for the College and addresses a significant gap in our holdings relating to early female Fellows.

After attending classes at Elsie Inglis’ Medical College for Women, McMillan graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1907 and, thereafter, was employed by the Foreign Mission Committee between 1908 and 1933. She was stationed throughout most of her Indian service in the British district of Ajmer, Rajputana.

After living and working with two female colleagues in a rented house, which they kitted-out to serve as a hospital, dispensary and residence, McMillan went on to play a key part in the founding and development of the Women’s Mission Hospital in Ajmer, which opened in 1916.

Helen McMillan, first Scottish female Fellow of RCSEd

Helen McMillan, first Scottish female Fellow of RCSEd

McMillan acquired wide-ranging and advanced surgical skills, including experience in facial reconstructive surgery. In regular and detailed correspondence with her family, she conveyed both the clinical intricacies of her operations and accounts of her patients; her letters reveal a deep compassion for those in her care. Her skill as a surgeon became well known and she was frequently called to treat patients all over Rajputana. McMillan’s work extended to the delivery of numerous babies and the coordination of crucial vaccination programmes, alongside a commitment to educating local women in nursing practice.

Overseas medical missionary work demanded exceptional resilience in the face of challenging climates and exposure to tropical diseases. In her early years in India, McMillan often wrote of the unfamiliar environment, recounting how every night she would use a lantern to check the area around her bed for snakes and scorpions. On occasion she even discovered lizards under the covers. The demands of operating in an isolated and under-resourced environment were also considerable. In one letter she wrote: “On Monday I went to Hospital, did an operation … There was not a clean apron at hand so what do you think I was arrayed in? An old nightdress of my own which I had given to the hospital as old linen! The nurses seemed to think I was quite grand looking”.

During World War One, McMillan was seconded to Bombay, where she was one of a number of female doctors who ran the Freeman Thomas Hospital. From 1924, she acted as Professor of Surgery at Lady Hardinge Medical College in Delhi before returning to Ajmer. Between 1927 and 1933, McMillan’s work in Ajmer overlapped with that of her sister, Margaret, a doctor who had also graduated in Edinburgh and entered the missionary field. In 1933, after a long and successful career in India, McMillan moved to Worcestershire to care for her other sister, Jean, and worked as a GP until her retirement.

Throughout her time in India, McMillan immersed herself in the local culture. She learned Urdu and Hindi and travelled extensively to explore the country when she was able to take a break from work.

She was also deeply committed to her faith. McMillan devoted considerable time to leading Sunday school classes and embraced the evangelical responsibilities that were integral to missionary work. For Christian missionary societies, the dissemination of the Gospel was a constant priority that underpinned all aspects of their work, including medical missions, hence the frequent reference to medical missionaries as ‘preaching healers’. However, the more aggressive evangelism of earlier missions gradually gave way to a greater emphasis on physical health over spiritual conversion. And, ironically, while women were entrusted by male missionaries to practise medicine and even surgery, they were afforded far less freedom when it came to preaching, where their spiritual roles were often restricted.

Preparing for an operation, India - McMillan family archive

Preparing for an operation, India - McMillan family archive

While the work of female medical missionaries is understood through a humanitarian lens, it is embedded within a complex historical context shaped by missionary societies and the broader structures of European colonialism. These women were pioneers practising medicine, performing surgery and providing essential healthcare at a time when such roles were frequently denied to them in their home countries. Yet their work in colonised regions was part of the colonial power dynamics that defined the era.

Medical missionaries often sidelined local knowledge and practices. While many saw themselves as sincere helpers, motivated by a genuine desire to serve, their efforts were often shaped by paternalistic attitudes and limited cultural understanding. Local resistance to western medicine and Christianity was frequently dismissed as ignorance rather than seen as a different worldview. There is a broad tension at the heart of medical missionary work: a sincere commitment to healing and care, shaped by the power imbalances and cultural assumptions of the colonial world.

The personal writings of individuals like McMillan offer valuable insight into these dynamics. She was a prolific letter writer and her archive holds important material for understanding both the medical and social dimensions of missionary work. Her correspondence provides rare evidence of the experiences of the earliest qualified female surgeons working overseas. It promises to be a rich resource for historians of medicine and empire, and I look forward to making it accessible to researchers.

Medical assistance as a prisoner of war

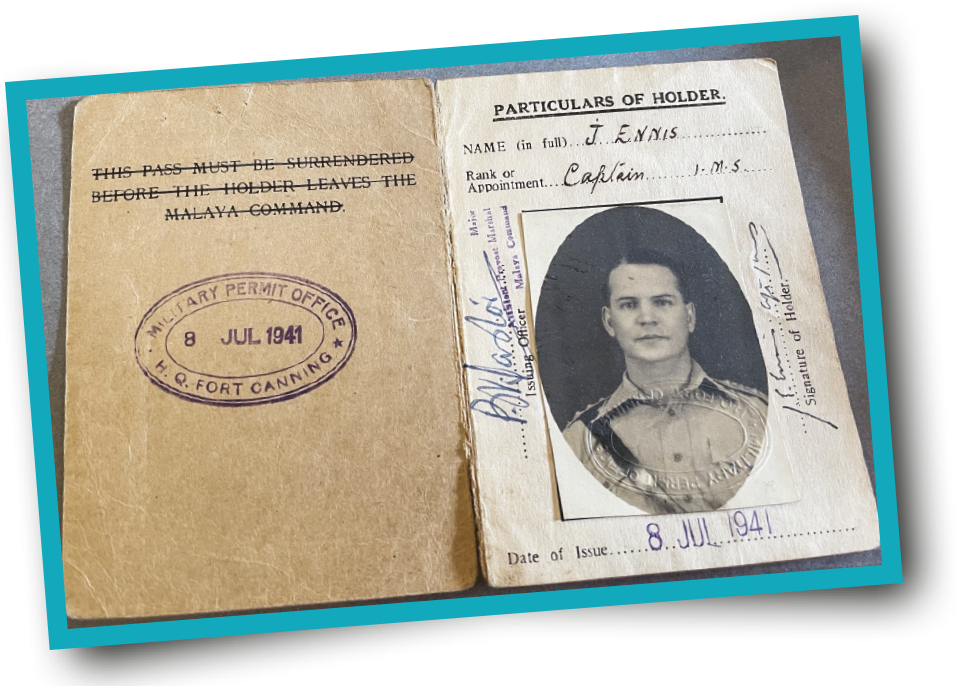

A newly gifted collection reveals the remarkable life of Captain Jack Ennis

The Heritage department has been gifted a unique collection from the family of Captain Jack Ennis, a prisoner of war under the Japanese in Singapore during the Second World War.

Ennis studied medicine and surgery in London, where he gained useful experience working at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. With a growing interest in pathology and his experiences of childhood in India, he applied to the Indian Medical Service.

After training with Royal Army Medical Corps recruits in England, he took up a position as a medical officer in India in 1939. With the growing threat of war, he was diverted to take control of the Far East Pathological Laboratory in Singapore in late 1939. There he met his future wife, Edinburgh-born nurse Marion Elizabeth Petrie.

After the fall of Singapore in February 1942, Ennis was imprisoned in military barracks, and later moved to other camps. Elizabeth was imprisoned with international civilians in the Changi gaol, where she continued nursing.

The extraordinary collection includes detailed diaries that Ennis kept at great risk. These give an insight into the physical and mental fatigue of life as a POW.

In an entry from 13 February 1944, he wrote: “Food is getting steadily worse. I am perpetually hungry – we don’t seem to be able to get enough rice”. The diaries reveal the desire for news from the outside world – rumours were rife and the daily ‘weather report’ was code for updates on allied activity.

The prisoners put on lectures, sports and theatre shows to entertain each other but hunger was never far from the POWs’ minds. An important pastime for Ennis were the Clinical Meetings of the Changi Medical Society, which provided lectures on current medical issues, history lectures and case studies. He wrote of one meeting, “turned out quite a success, too many cases shown, an interest in food spoilt it a bit”.

The conditions inside the camp were difficult but Ennis and his team managed to continue to run a pathology laboratory, including running thousands of tests and full post-mortems.

From the diaries, we can see that his camp started receiving returning ‘work parties’ from the infamous Thai-Burma railway, where the conditions were horrendous. In one entry, Ennis wrote: “76 Aussies came in to hospital this morning. Very emancipated and pale. Came down from Bangkok … treatment upcountry is dreadful, many deaths due to exposure. Poor food, ill treatment, malaria, dysentery. Cholera, and phagedna [tropical ulcer] for which limbs have to be amputated”.

Ennis also managed to keep detailed post-mortem reports. These give a grim insight into the suffering of the POWs, showing conditions such as dysentery, malaria, beriberi and pulmonary tuberculosis. These post-mortem and laboratory notes are a fantastic and very rare resource from this period and are now preserved for future research in the College Archives.

The museum holds special mementos kept by Ennis, including his medical armband, shoes made of bamboo and his Japanese name tag. The wider collection also includes drawings, telegrams home to family and letters from Elizabeth.

Perhaps most poignant is a letter Ennis received after the war from a guard named Hayashta, who apologises for his conduct: “How can I ask you to forgive me for what I did to you during the period of captivity in Singapore.” Exhibiting remarkable compassion and forgiveness, there is a letter in which Ennis offers support for soldiers from the Indian Army, who were used as sentries for the POW camps.

The museum will add this fantastic collection to its permanent galleries on 15 August to mark the 80th anniversary of victory in the Pacific.

Further reading

Doctor Behind the Wire: the Diaries of POW, Captain Jack Ennis, Singapore 1942–1945 by Jackie Sutherland

Read more