Fresh ideas

Anusha Adeline Hennedige discusses what she learned during

an insightful four weeks spent on a Fellowship in India in 2022

Anusha Adeline Hennedige: Consultant Paediatric Craniofacial and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Alder Hey Children’s Hospital

Afour-week maxillofacial Saleem Khwaja Memorial Fellowship in Paediatric Surgery in India gave me the opportunity to witness the delivery of healthcare in a different country and culture. In the current climate of strikes, lack of beds, medication shortages and demoralised NHS workers, this placement was a breath of fresh air, where clinical work and patient care is not clouded by bureaucracy.

Both hospitals were private institutions, and this gave me a perspective on the pros and cons of privately versus publicly funded hospitals. Healthcare is never black and white and should instead be a hybrid of the two systems to cater for the heterogeneity of populations.

Novel approach

For the first two weeks I observed Dr Subramoniam Balaji at Balaji Dental and Craniofacial Hospital in Chennai – an impressive one-man practice with more than 100 employees. As a singly qualified dental surgeon with a background of advanced training in plastic surgery, he is an ambitious individual who is involved with multiple dental and craniofacial organisations. As well as treating high-profile and international patients, he publishes widely.

Dr Balaji also advocates the use of internal distractors to manage hypoplastic conditions. He uses only internal distractors for midface advancement and achieves impressive results. He advocates internal distractors for managing Pruzansky type I–III mandibles and temporo-mandibular joint ankylosis. His application of distraction osteogenesis (DO) is more extensive than I have witnessed in the UK and produces results in patients who in the UK we would not consider for DO – for example, Pruzansky type III patients.

In craniofacial surgery, facial asymmetry and dysostosis is a common presentation, which in the UK is usually managed with allogenic materials such as Medpore or PEEK implants. In India allogenic material is less commonly used due to cost and high levels of infection. They have been innovative in the use of autogenous bone to reconstruct and manage facial asymmetry. At Balaji Hospital there was judicious use of rib graft and bone-morphogenic protein for managing clefts and as an adjunct in patients with orthognathic problems and facial asymmetry.

At the Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, led by Chief Maxillofacial Surgeon Dr Pramod Subash, I was introduced to the concept of orthomorphic surgery. It is a reverse bilateral sagittal split osteotomy with an extended genioplasty up to the ramus. It is a camouflage procedure that does not alter the occlusion but addresses the facial asymmetry.

In the UK we tend to adopt a practice of presurgical orthodontics, which can be a 24–30-month process, achieving perfectly aligned dental arches and facial harmony at the end of treatment. The priorities and patient demands are different in India. Although function is of prime importance, facial aesthetics has a significant bearing on social factors, family status and marital opportunities in a culture where arranged marriages are the norm. This has to be balanced with cost and time. Patients will accept their existing occlusion for improved facial symmetry in a shorter period of time.

Left to right: Subramoniam Balaji, Ramesh Singaravelu (anaesthetist) and Anusha Hennedige at the Balaji Hospit

Left to right: Subramoniam Balaji, Ramesh Singaravelu (anaesthetist) and Anusha Hennedige at the Balaji Hospit

Culture of excellence

Patients travel from beyond the borders and shop around India for the right surgeon who will perform their procedure for a fair price and in a reasonable timeframe. Having said that, patients also go in search of the best doctor who they trust and has a global reputation. This fosters a culture among doctors to develop themselves and encourages innovative thinking, flexibility and competitiveness, which leads to the development of ambitious doctors who can offer a service that throws their competitors out of the water.

I believe this is an aspect of healthcare we lack in the UK. Although the NHS comes with altruistic and democratic qualities, its homogeneity across the various Trusts tends to foster mediocrity as opposed to excellence. There is a culture within the NHS that carries the mentality of ‘do the minimum to get the job done’. This is a dangerous place to be when it comes to healthcare and there are aspects of care we can learn from our Indian colleagues. But this is an issue that goes far beyond the surgeon, team or Trust. It is a national crisis in the UK and it is time we looked at our neighbours to see how best to modify our delivery of healthcare in the UK.

Having said that, it is remarkable we have a healthcare system that enables our team to treat a child from birth through to adulthood for their craniofacial condition involving hundreds of healthcare workers and more than 1,000 hours of NHS time without asking the family for a penny. There is a balance we need to strike and that time is imminent.

Some of the complex procedures we perform in craniofacial surgery are Le Fort III (LF3) advancements and monobloc advancements, which can carry a 50% risk of morbidity. They involve osteotomies and multiple areas for surgical access. Patients wear a RED frame for four months of distraction and consolidation. The aims of surgery are to relieve obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), eye protection and improve facial aesthetics.

“The culture among doctors encourages innovative thinking, flexibility and competitiveness”

To avoid the use of the RED frame for four months, the Amrita maxillofacial team adopted the use of the push-pull technique which is not a new concept to the craniofacial surgeon, but has not been popularised in the UK. The concept involves a RED frame where the ‘pull’ element and the ‘push’ elements are bilateral cranial distractors. After a period of distraction (two to three weeks), the RED frame and the activation arms are removed and the distractors left in situ. Not only is this more comfortable for the patient, it reduces the risk of entry/pin site infection.

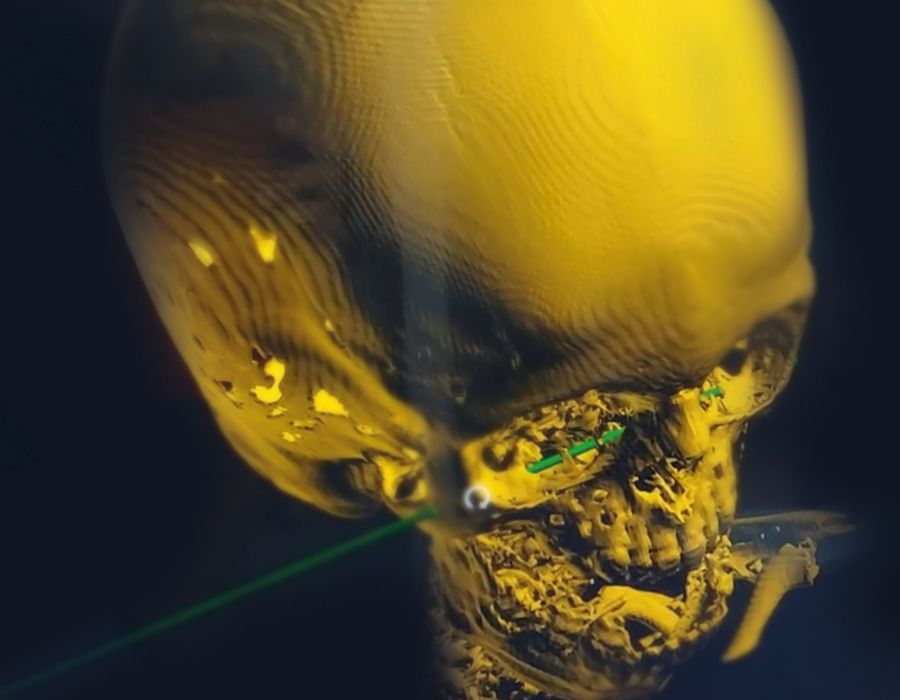

At the Amrita Institute the team use a robot for assistance with their younger patients who require midface advancement. They use the robot to design a trajectory through the midface using a transfacial pin to distract the midface in younger children who suffer from obstructive sleep apnoea or proptosis. The benefits of using the robot assistance is that you can avoid key structures such as the globe and toothbuds. They (with a French surgeon) developed an ingenious distractor device to attach to the transfacial pin for distraction. In addition, they use minimal access with three 1cm incisions on the face to complete a LF3 osteotomy.

Planning trajectory of midfacial pin on the robot to avoid vital structures and toothbuds

Planning trajectory of midfacial pin on the robot to avoid vital structures and toothbuds

In the UK these children either undergo an early monobloc or midface advancement, which has significant co-morbidities, or wait until they reach at least the age of eight and temporise the signs and symptoms with nasopharyngeal airways, non-invasive ventilation, tracheostomies and tarsorrhaphies. This is the first reported use of robotics in the realm of paediatric craniofacial surgery.

New perspective

This Fellowship provided me with a new perspective as an individual and surgeon. It reinvigorated my enthusiasm for change and advancement of paediatric craniofacial surgery, and bolstered my confidence in introducing new techniques to the UK.

I am humbled by the skills and knowledge of the maxillofacial surgeons in India and hope to emulate their work in my practice in the hope of serving our patients in a better and safer way. I thank the RCSEd and the Saleem Khwaja Fellowship and family for giving me this opportunity to advance the face of paediatric surgery in the UK.